The City of London has over 150 open spaces from city gardens to pocket parks. Many are former graveyards, and Postman’s Park fits that category.

It is a shady garden with plenty of benches to stop with your takeaway lunch and enjoy the calm away from the City streets. It’s also a pleasant cut-through from King Edward Street to St Martin’ s-le-Grand, close to the Museum of London and St Bartholomew’s Hospital. There’s seasonal planting and some features such as a pond and a sundial. Plants of particular interest are the large Japanese banana (musa basjoo) which flowers in late summer and the dove tree (davidia involucrata).

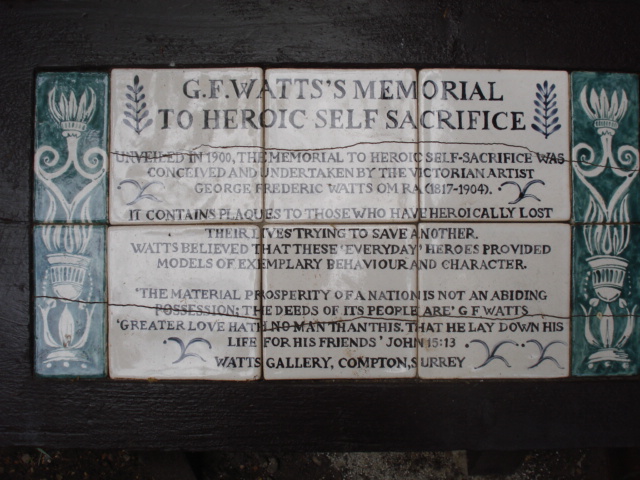

Today, this peaceful garden is most well-known for the Victorian Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice – poignant plaques to remember everyday heroes who lost their lives while saving another. It records the individual acts of bravery of men, women and children.

What’s That Got to Do With Postmen?

In 1829, the General Post Office moved into a building on nearby St Martin-Le-Grand, and it remained the main post office for London until 1910. This was the UK’s first purpose-built post office, so had a large workforce. When the Park was created in 1880, the post office was continuing to expand in the area. The Park soon became a popular place for workers to bring their lunch or to rest outdoors so became known to all as the “Postman’s Park”.

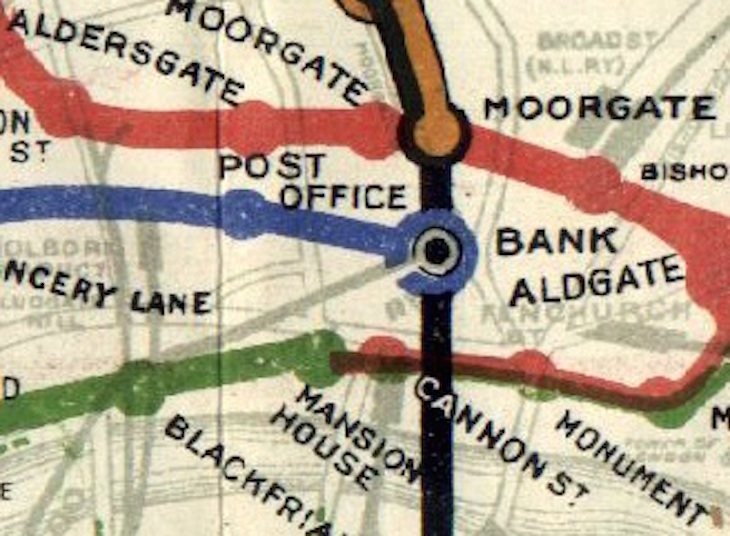

The tube station we know today as St Paul’s was originally called ‘Post Office’ station when it first opened on the Central London Railway in 1900. While it is very close to St Paul’s Cathedral, that obvious name choice was already taken as there was a St Paul’s railway station – the one that’s now called Blackfriars.

Former Burial Ground

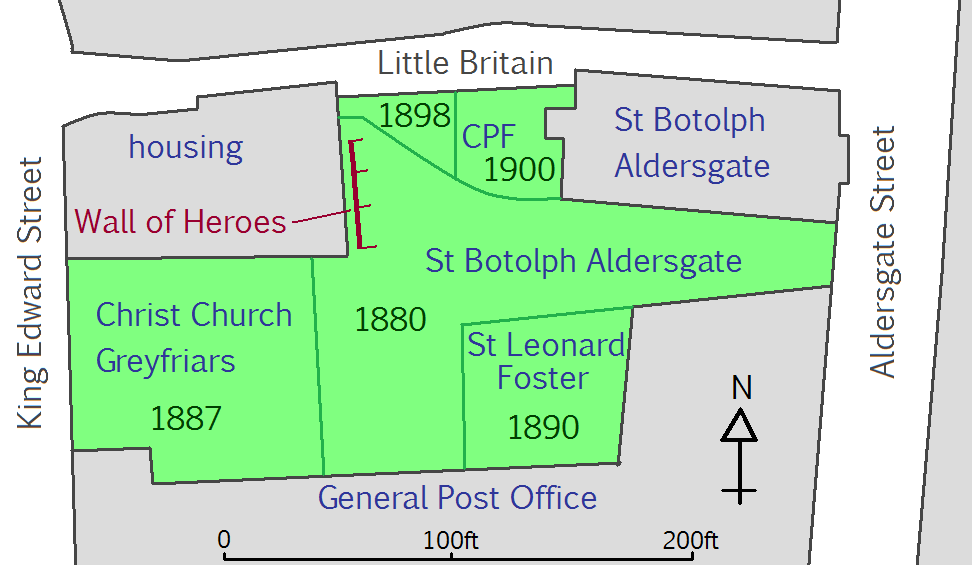

Postman’s Park is one of the largest churchyard gardens in the City of London. It’s on the site of an amalgamation of three City of London burial grounds: ‘Christchurch Greyfriars’, ‘St Leonard, Foster Lane’ and ‘St Botolph, Aldersgate’. Today, the only remaining church is the Grade I-listed St Botolph’s Without Aldersgate church which still stands in the park grounds.

It was within the boundaries of the parish that the St Botolph’s Aldergate church serves that both John and Charles Wesley underwent their evangelical conversions. On the Aldersgate Street railings, there is a ‘Tablet Erected to the Glory of God in Commemoration of the Evangelical Conversion of Revd. John Wesley’. It states:

This tablet is erected to the glory of God in commemoration of the evangelical conversion of the Rev. John Wesley, MA, on May 24, 1738. (The site of the meeting room of the religious society was probably 28 Aldersgate Street), and of the Rev. Charles Wesley, MA, on May 21, 1738. The site of the house is near St Bartholomew’s Hospital (no. 12 Little Britain).

Erected by the International Methodist Historical Union, May 24 1926.

Within the Park, it might be easy to miss this former use until you notice a number of gravestones that hide behind the foliage, grouped against the walls.

Serious outbreaks of cholera in 1831 and 1848 had overwhelmed the crowded cemeteries of London. This burial ground had been in use since the 14th century, so there was a massive shortage of available burial space. Graves were being used for multiple bodies with just a layer of soil between. It was soon too difficult to bury another body without disturbing those already in the grave.

In the early 1850s, the Metropolitan Burials Act prohibited new burials in central London, so this burial ground closed in 1853. Large cemeteries outside of the centre were used instead; such as Highgate or Kensal Green.

In 1858, the churchwardens of St. Botolph, Aldersgate, announced that they intended to “…plant, pave, or cover over the churchyard and burial-ground.” Parishioners were advised that they could move the remains of loved ones to another cemetery at their own cost. The initial deadline (an awkward word choice here) was 20 December 1858, but it was such a difficult task that it actually took decades to clear the graves. The Park finally opened to the public on 28 October 1880.

As well as the gravestones and a few tombs, the original gates at the Aldersgate Street entrance have been kept. A less obvious sign of the former use is the raised height of the Park as you have to climb a few steps to enter. Burial grounds were often elevated above street level due to the many stacked graves.

The Park’s listed structures include the church, the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, those original gates and railings plus this drinking fountain on Aldersgate Street. (I’ve also read there are remains of the City’s Roman wall, but I’ve never noticed it.)

Metropolitan Public Gardens Foundation

By the late 1890s, the Park was being considered for building development. The northern section was under the jurisdiction of the newly formed City Parochial Foundation who were keen to sell. The public outcry at the decision persuaded the Foundation to offer to sell the land to St Botolph’s for £12,000.

A fundraising campaign – said to commemorate Queen Victoria’s 1887 Golden Jubilee – won the support of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association. Contributions were received from local businesses, concerned citizens and both the London County Council and the corporation of the City of London.

The target was reached the garden was extended in 1900 with additional land between the existing Park, the rear of the church and along Little Britain.

George Frederic Watts

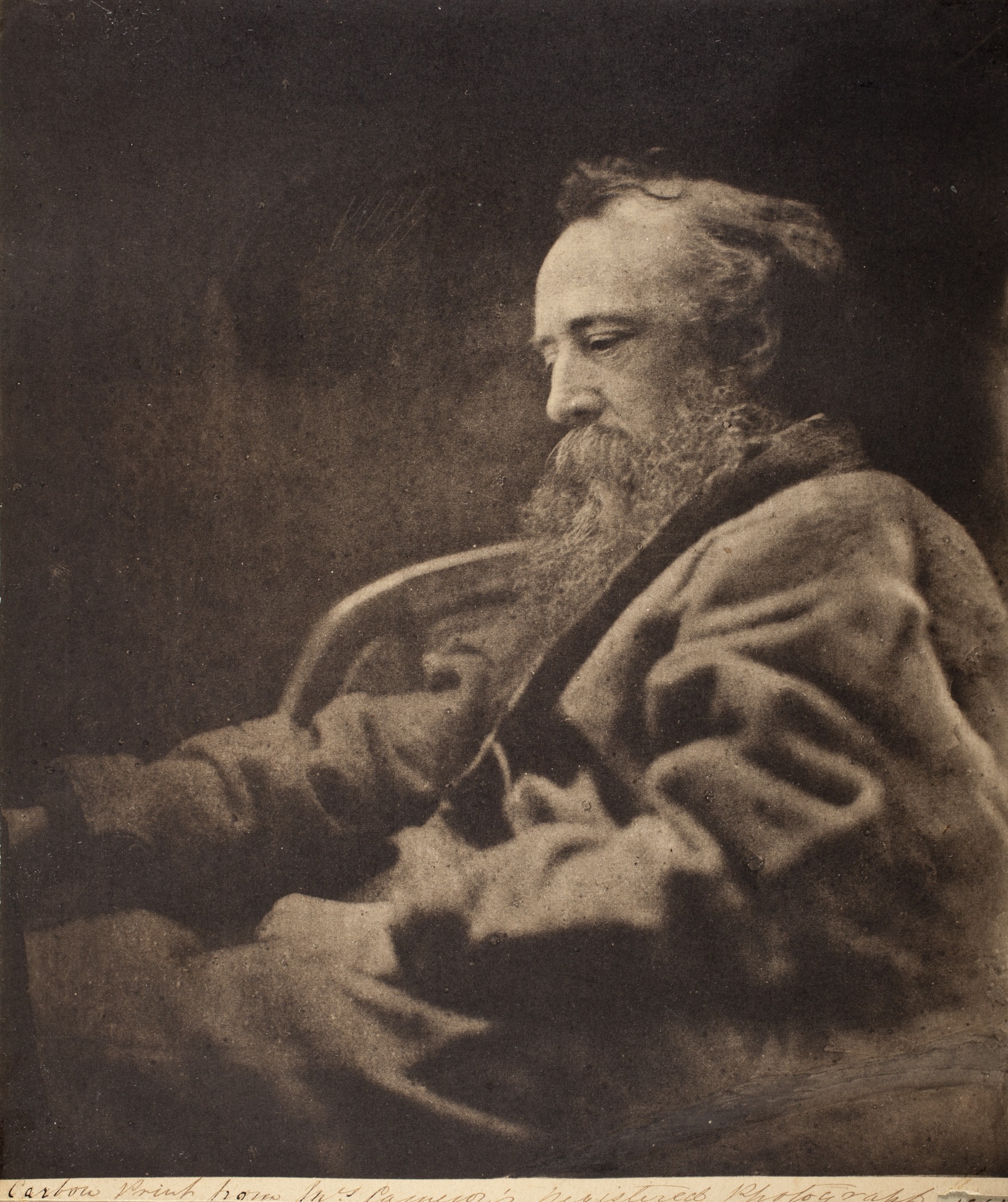

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) was a radical socialist as well as a respected Victorian artist and philanthropist. (Son of a London piano maker, he apparently shared the same birthday as composer George Frederic Handel – hence the name.)

From the 1870s, Watts dedicated substantial creative effort to working in sculpture. He created the statue of Lord Holland in Holland Park and his most famous work, Physical Energy, occupied him up until his death in 1904. The original gesso grosso model can be seen at the Watts Gallery in Surrey. Four versions were cast in bronze, and we can see it in Kensington Gardens.

Watts was very sympathetic towards the dreadful living conditions of the urban poor and made no attempt to hide his dislike of the greedy upper classes.

In 1887, he wrote to the Times proposing a park commemorating ‘heroic men and women’ who had given their lives attempting to save others. He felt it would be a worthy way to mark Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year. His letter was published on 7 September 1887 under the heading ‘Another Jubilee Suggestion’.

Inspiration

London already had lots of statues and memorials to military heroes and well-known names, so Watts wanted this memorial to be a tribute to the heroic Londoners he read about in the newspaper. Those who didn’t expect to be honoured. The people who would be quickly forgotten even though their actions saved a life. He felt once the news report noted the deaths, it was too quick to move on without reflecting on that ultimate sacrifice.

As well as being somewhere to keep a record of these courageous events, Watts wanted the memorial to inspire those who came to see it to go on to lead a better life. He wanted visitors to see the plaques as examples of model behaviour to be undertaken by people of sound and decent moral character; to see the bold acts as a product of an exemplary life rather than just a single brave moment.

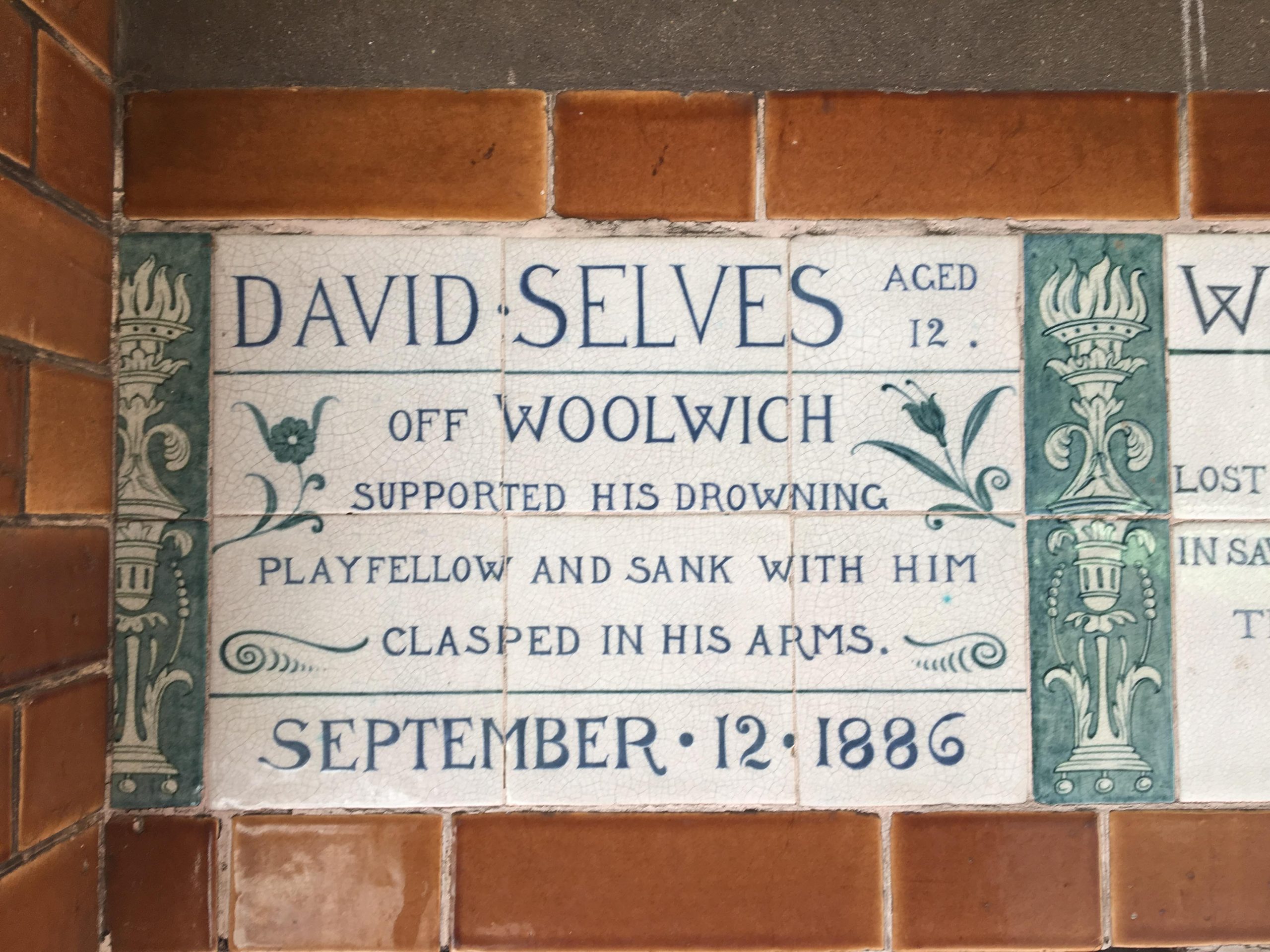

The memorial predominantly chose ordinary working-class people who would have remained largely ‘hidden from history’ were it not for the circumstances of their death.

Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice

The idea for the memorial didn’t initially get much support. Watts tried campaigning for the memorial to be erected in a variety of places including Hyde Park without success.

A friend of Watts suggested the idea to the then vicar of St Botolph’s, Henry Reginald Gamble (1859–1931), and the relatively new Postman’s Park was chosen as the location.

Watts agreed to construct the memorial at his own expense. His initial design was for a covered cloister around three sides of a quadrangle, with the roof supported on stone or timber columns. The Metropolitan Public Gardens Association wanted to be consulted, so the design was adjusted to be the 50-foot (15 m) long, and 9-foot (2.7 m) tall open wooden gallery with a pitched tiled roof, which greets visitors to Postman’s Park today.

It was completed and opened to the public on 30 July 1900. Sadly, Watts himself was too ill to attend the unveiling ceremony for the monument he had fought so hard to erect.

The Ceramic Plaques

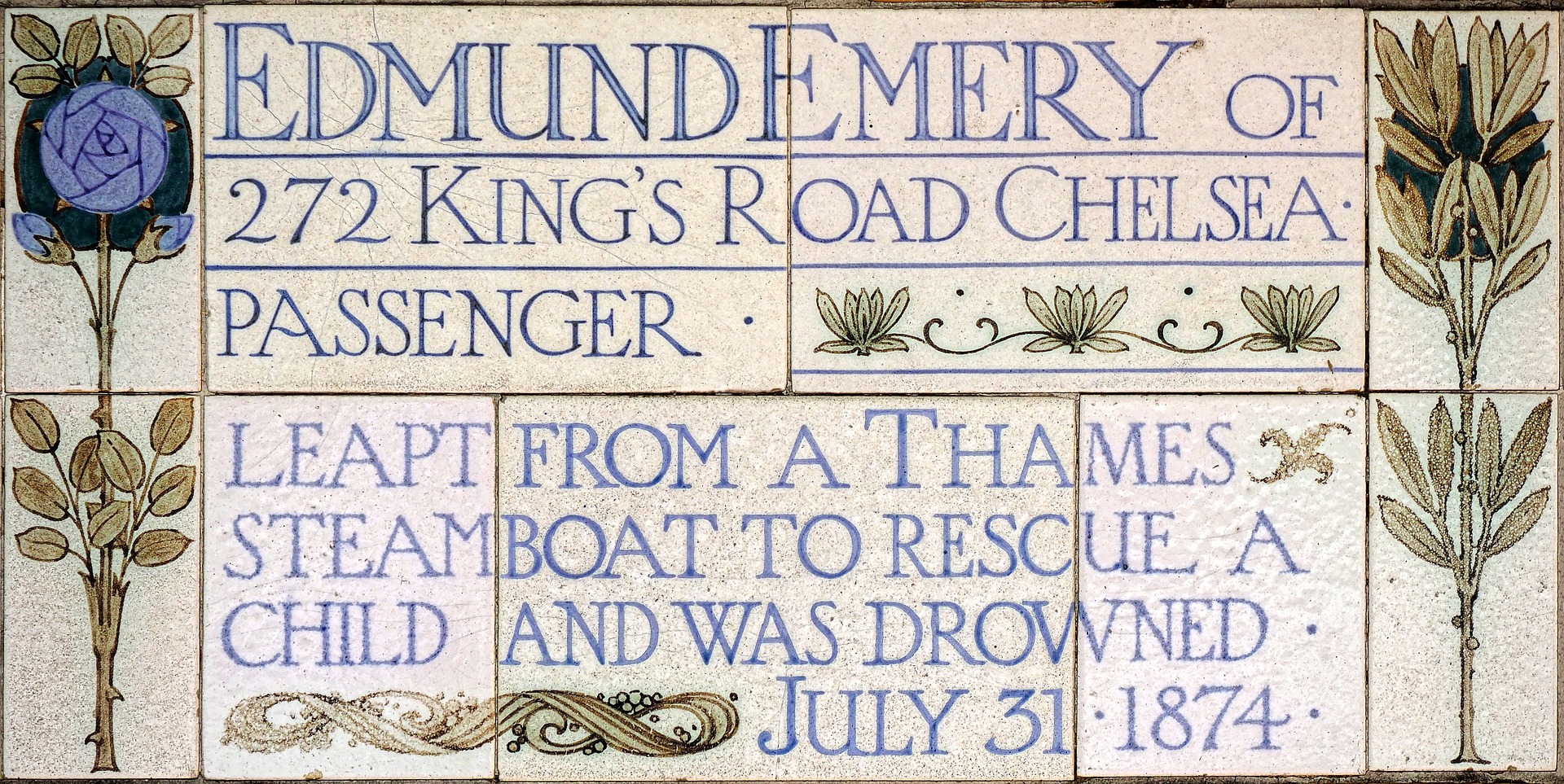

Like the unsung heroes chosen for the memorial, Watts wanted to keep things modest and simple with a ceramic tablet for each event noting the name, date and a little about what happened.

Despite having space for 120 ceramic plaques, there were only four on the memorial when it was opened in 1900 documenting an industrial accident, a train rescue, a loss at sea and a fire.

Watts continued to fund the memorial, and a further nine tablets were added to the wall in 1902, all of them manufactured by ceramist William De Morgan (1839–1917) – his last major commission.

George Frederic Watts died on 1 July 1904, but tablets continued to be added.

A further eleven, again manufactured by De Morgan, were installed, completing the middle row of 24 plaques. After De Morgan went out of business in 1907, Mary Watts commissioned Doulton of Lambeth for the second row of 24 plaques which were added in 1908. Apparently, Mary didn’t like the newer tiles as much, so there was no ceremony when they were installed.

More followed until 1931 when there were then 53 tablets on display.

Glazed ceramic tiles were clearly cheaper to produce than engraved stone. The design and styling of the tiles do vary although they all follow the same basic principle of green or blue lettering and a decorative motif on a white background. Some of the tiles are separated by a classical green design, and others have an Art Nouveau floral border.

How They Were Chosen

During his lifetime, G. F. Watts collected hundreds of newspaper cuttings of heroic acts. Transcriptions of these cuttings formed a catalogue from which cases were chosen for the memorial.

After Watts’ death in 1904, his wife Mary and a committee based within St. Botolph’s church decided which cases to commemorate. The criteria for inclusion were that a candidate would be from London and that the act of self-sacrifice must have taken place during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Mary oversaw the project for many years, but the memorial was all but abandoned when she died in 1938.

Watts is Remembered Too

As well as the tragic tales, each dedicated to an ordinary person who did something most extraordinary, there is an addition to remember the man who created the memorial.

George Frederic Watts died in 1904 at the age of 87. A special plaque designed by T.H. Wren was added to the memorial and unveiled in 1905. It depicts Watts holding a scroll with the word ‘heroes’ written on it. The caption below the figure reads ‘In memorial of George Frederic Watts, who desiring to honour heroic self-sacrifice placed these records here’.

The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice was given Grade II listed status in 1972.

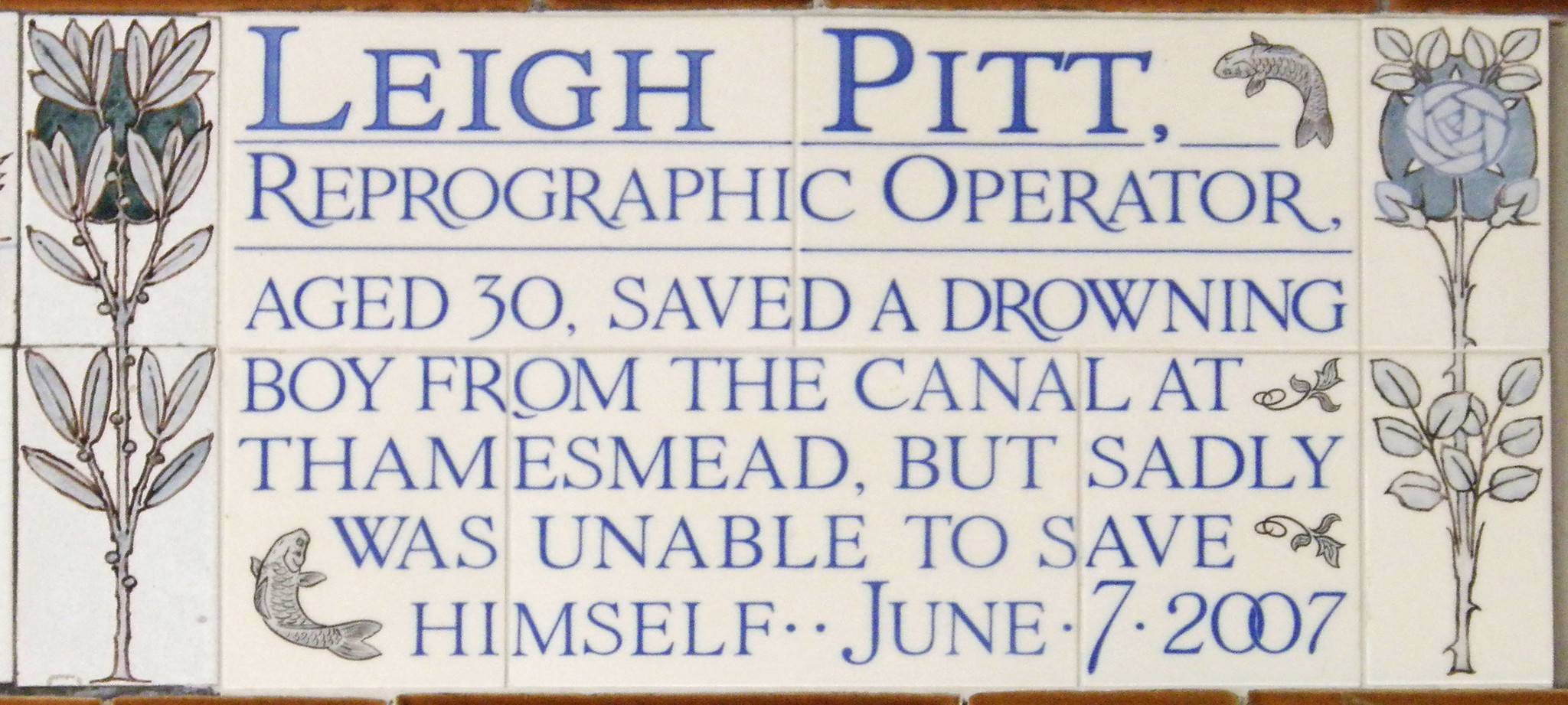

One Final Tablet

No further tablets were added for over 70 years. Then on 11 July 2009, a plaque commemorating Leigh Pitt was installed.

Pitt had bravely jumped into a Thamesmead canal to rescue a nine-year-old boy who had fallen in and was struggling to stay afloat. He held the child, Harley Bagnall-Taylor, above the water line before passers-by were able to rescue the boy, pulling him out with a hosepipe. Sadly, Pitt was unable to haul himself over the high canal walls and subsequently drowned.

Even though there are still 66 empty spaces available, in 2010 it was confirmed that no more tablets would be added to the memorial. The reasons behind this decision were that the memorial was a personal project of G. F. Watts and his vision and influence were intrinsic to its character. It was thought that the historical integrity of the memorial would be further compromised by additional tablets. Also that the memorial predated the modern honours system which now allows for posthumous recognition.

Hollywood

In 1997, playwright Patrick Marber wrote a production called ‘Closer’ which premiered at the National Theatre. The play was later made into the BAFTA- and Golden Globe-winning movie Closer starring Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts, Jude Law and Clive Owen.

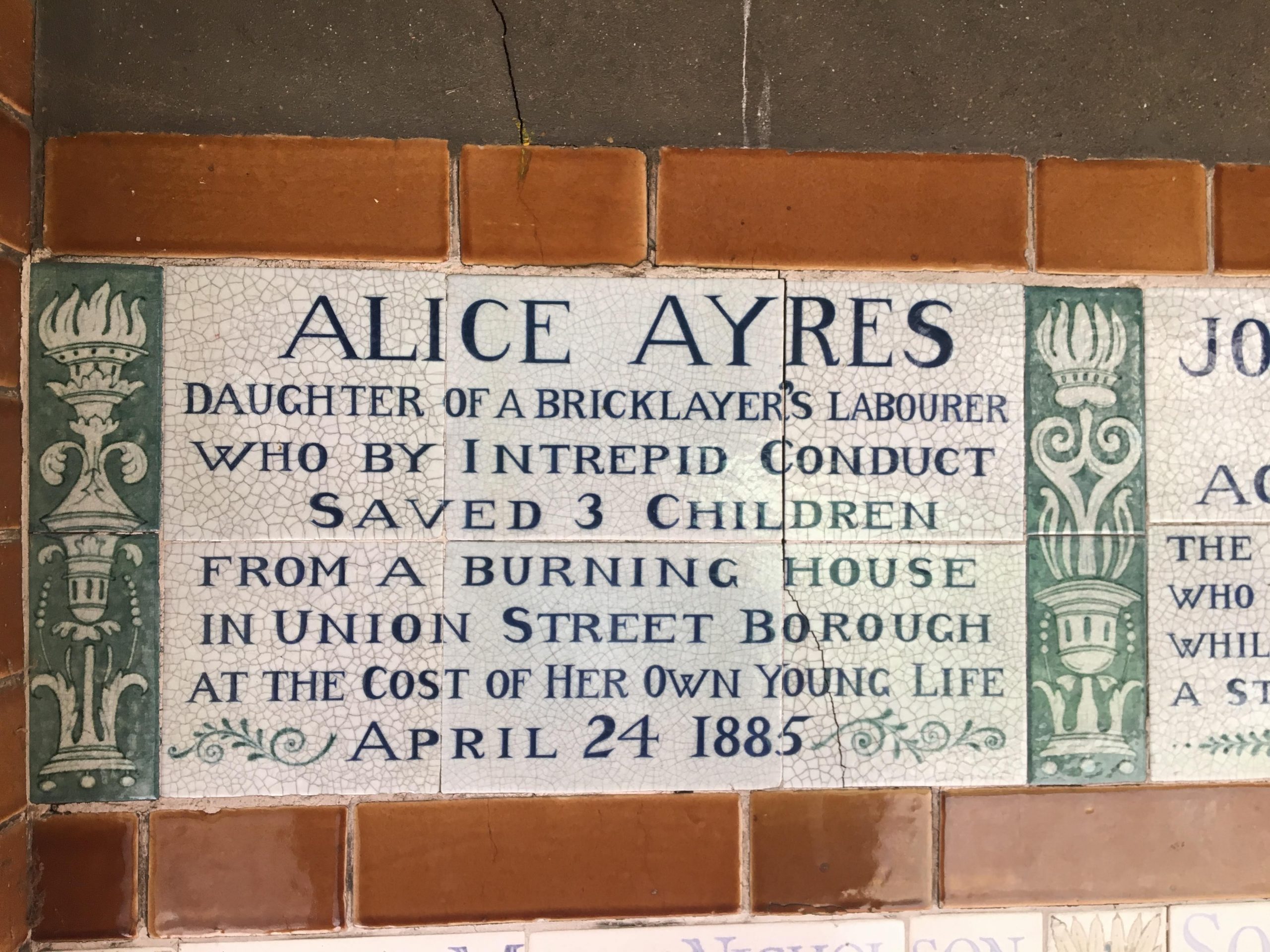

A key plot element of the story centres on Postman’s Park as Portman’s character uses a name from the memorial, Alice Ayres, to create a new identity.

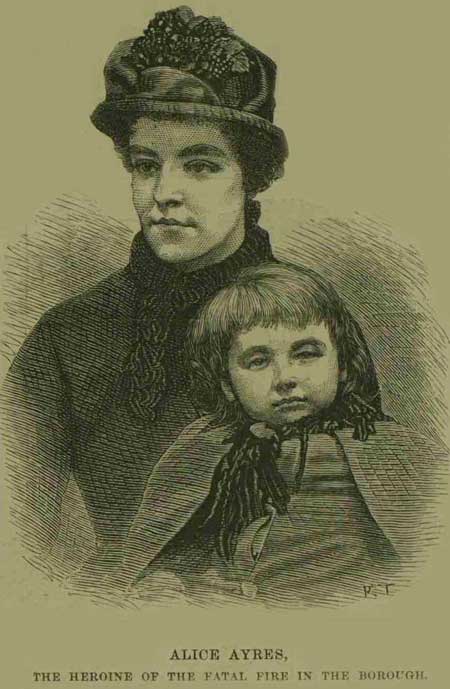

Alice Ayres

The whole memorial had come about as Watts had been so inspired by the bravery of Alice Ayres. In 1885 she had sacrificed her life to rescue her three nieces from a fire in Union Street, Borough.

A fire broke out during the night, and Alice had the forethought to throw a feather mattress out of the window. The crowd below held it up to catch the three children that Alice rescued. Sadly, when she jumped herself, she received terrible injuries and died two days later.

It was a horrific fire as the homeowner, Mr H. Chandler, his wife (Alice’s sister), and their son were burnt to death. The three girls were Edith, aged five, Ellen, four years old, and Elizabeth, three years old.

After her heroic death, Alice Ayres caught the public imagination. There’s a memorial to her in Isleworth cemetery, and a street in Borough was named after her in 1936.

The People

The 54 memorial tablets on the Watts Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice commemorate 62 men, women and children.

Sarah Smith

The earliest case featured is that of Sarah Smith – the stage name of Sarah Gibson (1845–1863) who was a pantomime artist. She died at an Oxford Street theatre in January 1863.

This tablet has a couple of mistakes as the accident was at the Princess’s Theatre and not the Prince’s Theatre. And it happened on 23 January and not 24 January. There is also some dispute as to whether she was trying to rescue her friend or was simply set alight at the same time. (These mistakes most probably happened as Watts used newspaper cuttings to find these tragic tales and the initial reports were inaccurate.)

A spark from a stage light set fire to dancer Anne Hunt’s dress, and Sarah rushed to help despite wearing the same thing. Apparently, it was Robert Roxby, the Stage Manager, who extinguished the flaming clothes with his Inverness cape (think of Sherlock Holmes, and you’ll know what that looks like). He assisted Anne first and then Sarah.

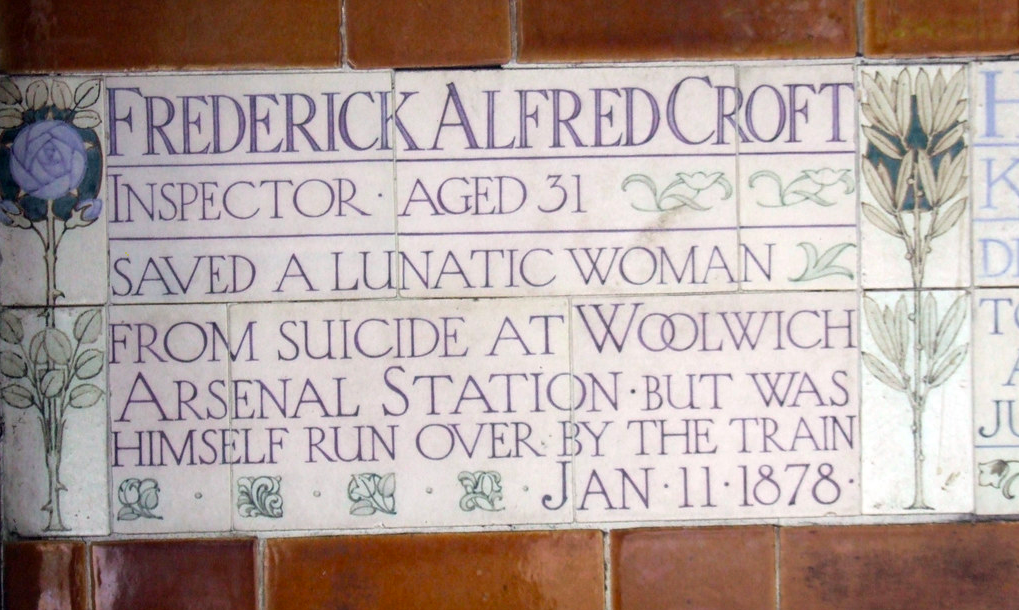

Frederick Alfred Craft

Another mistake is the name below. Frederick Alfred Craft’s name was wrongly spelt on the memorial, as Croft. Frederick Craft (1848–1878) was a Night Inspector on the South Eastern Railway.

While on duty at Woolwich Arsenal station on 11 January, there was an ‘insane’ woman called Eliza Newman being taken to Barming Lunatic Asylum in Maidstone, Kent. There were three officers with her: the relieving officer Mr Moore, infirmary matron Miss Wilkinson and another assistant. Even so, she broke free from them when the train approached.

There are conflicting reports on the finer details, but either Newman jumped onto the rails, and the Inspector leapt after her to push her away to safety. Or he seized her on the platform when she tried to get away and in the struggle, she knocked him onto the track as the train arrived. But either way, Craft was hit by the train severing both legs and one arm.

I always found the use of the word ‘lunatic’ upsetting on this plaque. After she was moved to the asylum, her rooms in Woolwich were cleared out, and she was found to be quite wealthy. Mental illness doesn’t restrict itself to ‘paupers’.

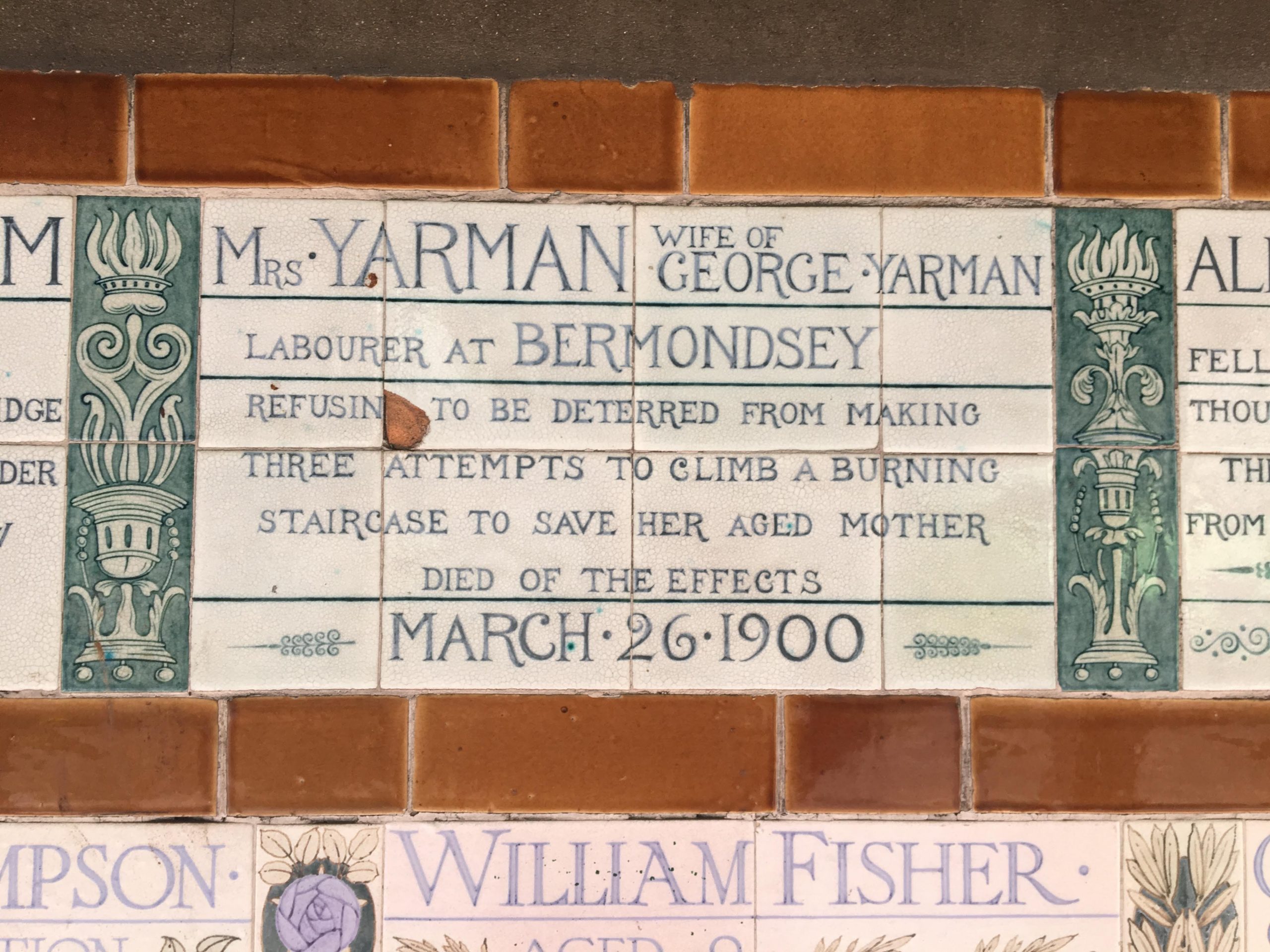

Mary Jarman

Another name spelt wrong is for Mary Jarman (1847–1900). (It also seems a shame that even in death she was identified by her husband’s first name rather than her own.) And a factual mistake is that she was attempting to save Elizabeth Eyre – her mother-in-law, not her mother.

They awoke in the night to find their house on fire and tried to rescue the 77-year-old woman who was still sleeping. Their astonishing efforts were ultimately doomed as both husband and wife had to jump from the building through a window and leave the old women to burn to death.

Three days later, 45-year-old Mary died from her extensive burns.

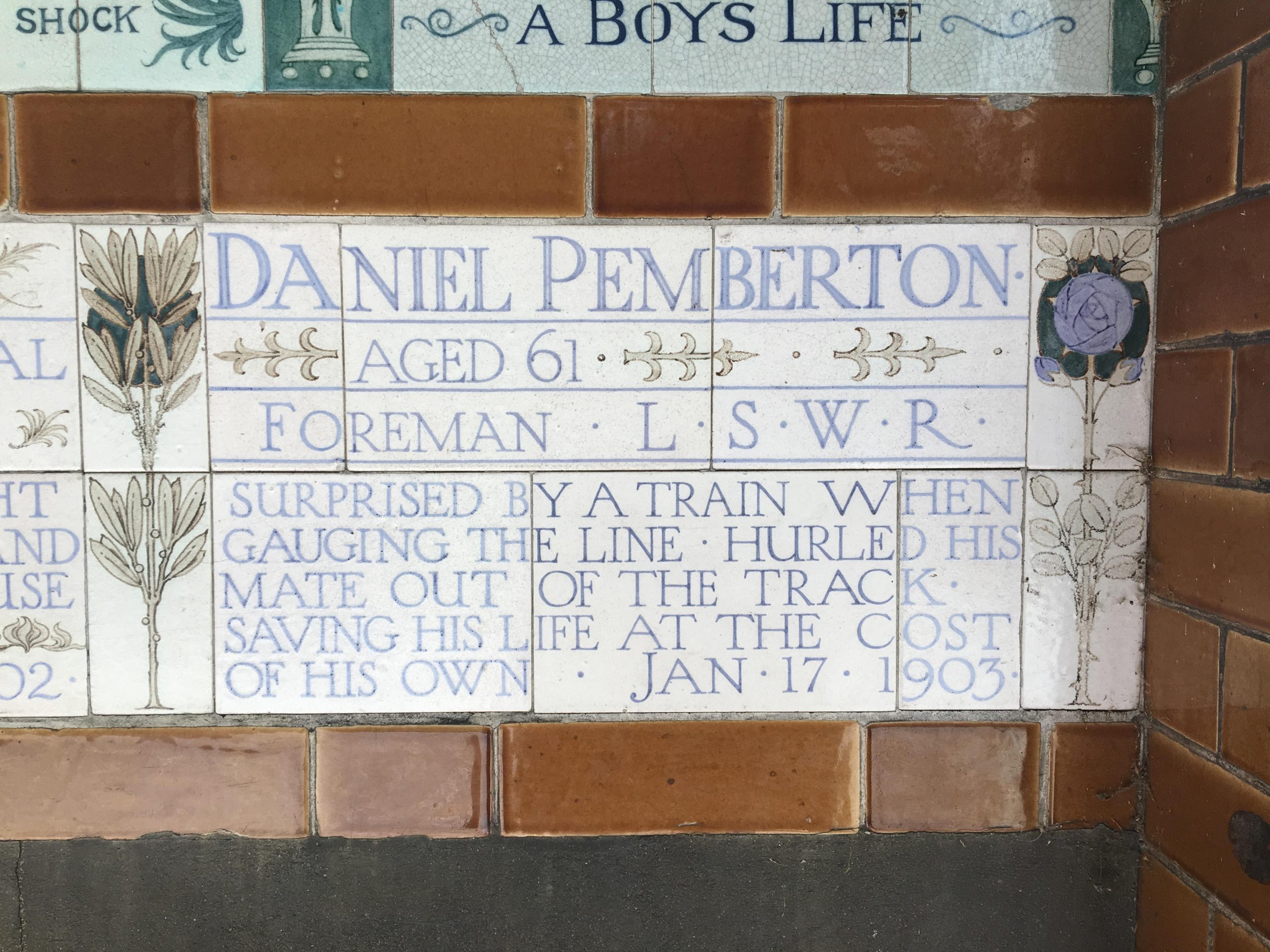

Daniel Pemberton

The oldest person on the memorial is sixty-one-year-old Daniel Pemberton (1833–1903) who died in another railway accident.

The ‘mate’ noted was Thomas Harwood who said at the inquest that he would have been killed by a train had not Pemberton pushed him out of the way. The train driver didn’t realise he’d hit anyone until his train reached Waterloo station. Both the driver and Harwood confirmed there was a lot of steam and smoke at the time.

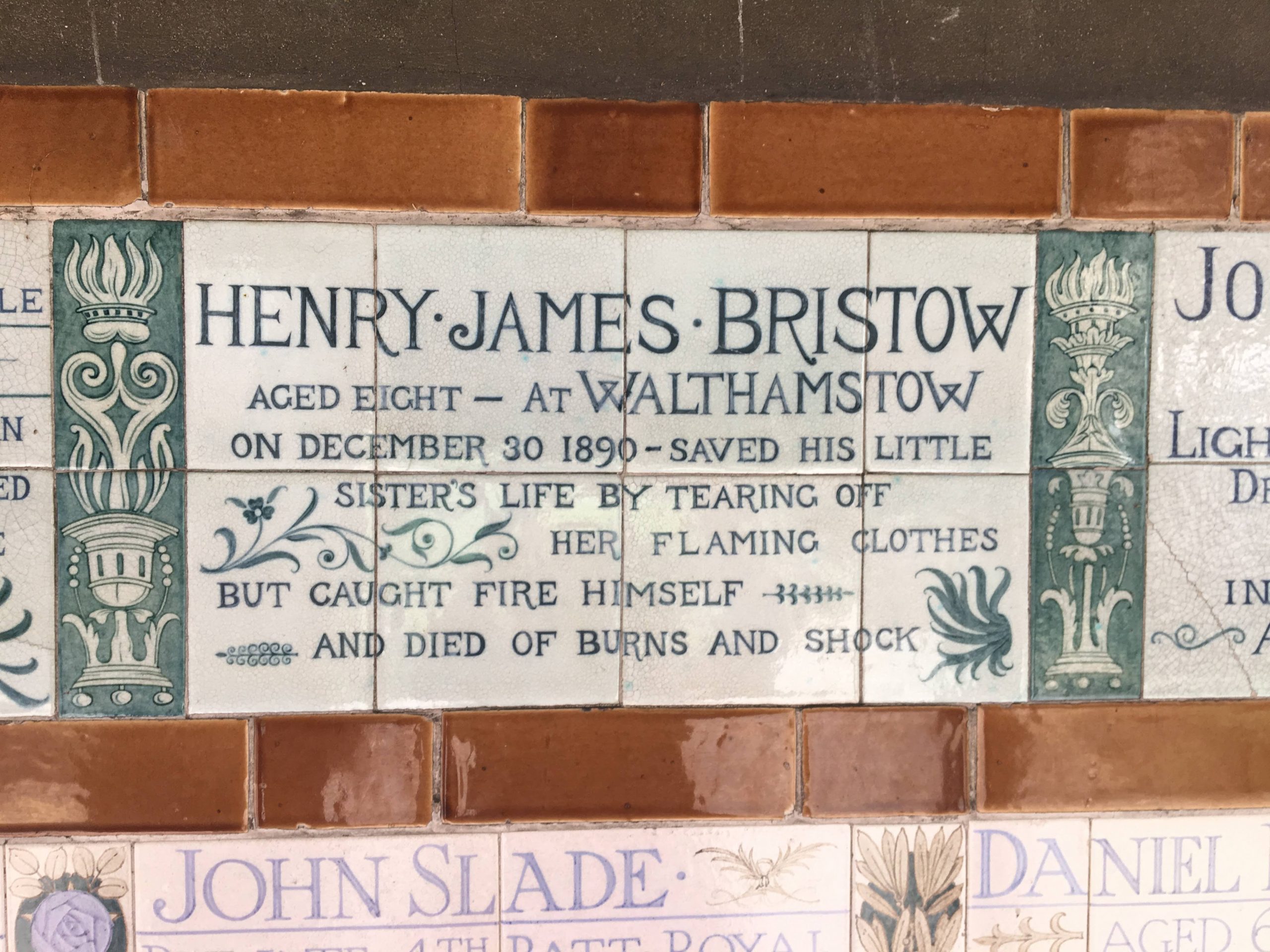

Henry James Bristow

The youngest individual commemorated is eight-year-old Henry James Bristow (1882–1890). While just a child himself, he saved his three-year-old sister’s life, but he died of burns and shock.

His mother had left the house on an errand. While out for just twenty minutes, the little girl knocked over a paraffin lamp, setting her clothes on fire. In saving her, Henry’s clothes caught on fire too. He was found naked, badly burned but still conscious so he could explain what had happened.

Both children were taken to the German Hospital in Hackney. Sadly, Henry died from his injuries in hospital, but his little sister made a complete recovery.

The house was at 7 Hawkesley Terrace, Walthamstow. I discovered there was a name change to Hawkesley Road in 1892/3 and it was renamed again in 1911 to become Southcote Road. I know the area well so wandered off to see if the house is still there but, I can report, it has long gone, and there are now flats at the location.

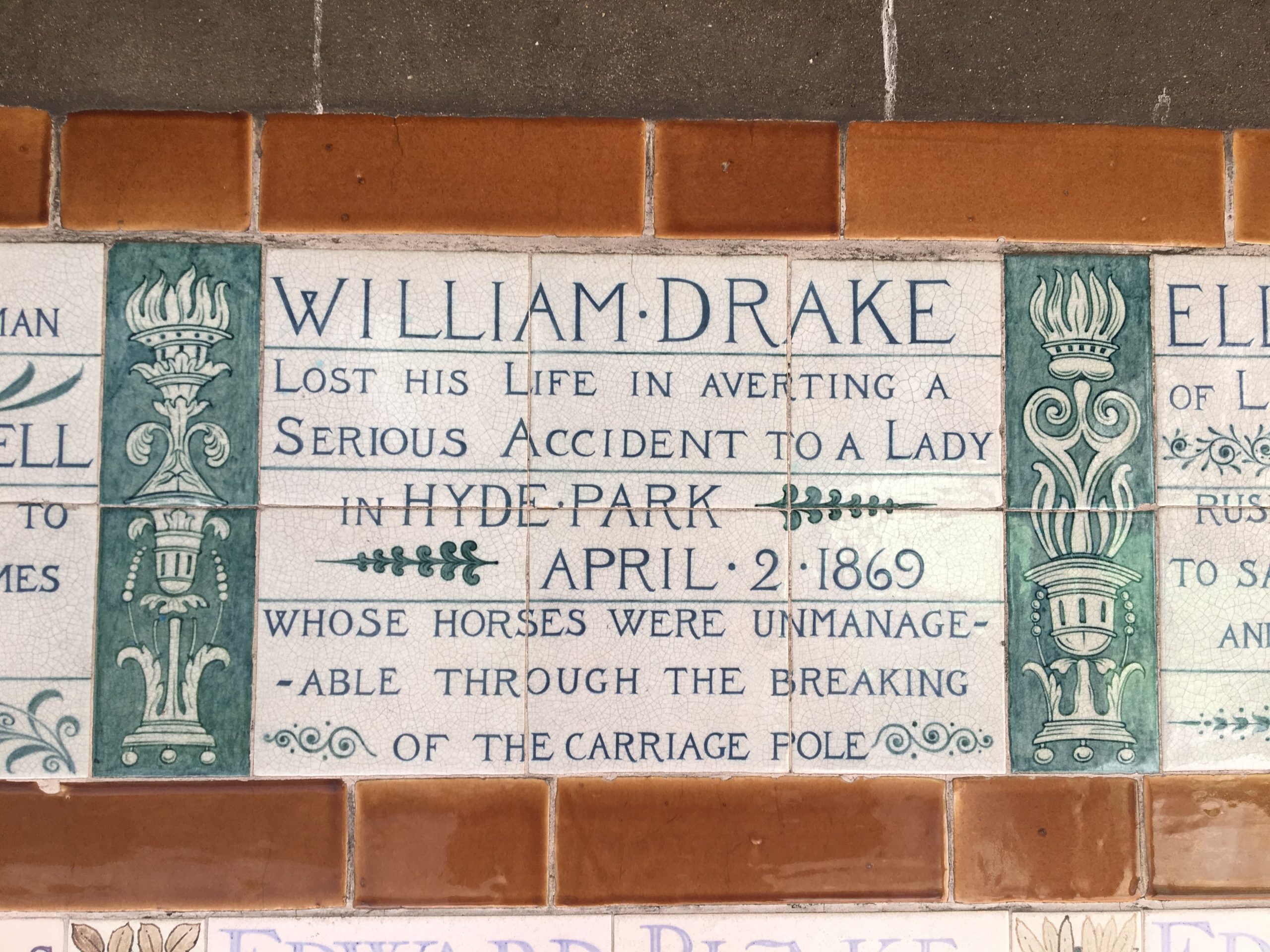

William Drake

The ‘lady’ who William Drake (1811–1869) saved was Thérese Johanne Alexandra Tietjens (1831–1877), a leading Victorian opera and oratorio soprano. Many opera historians consider her to have been the finest dramatic soprano of the second half of the 19th century. Born in Hamburg, she had moved to London in 1858.

Mademoiselle Tietjens and a friend were entering Hyde Park in a horse-drawn Brougham carriage, through Stanhope Gate off Park Lane. A wagonette crossed in front of the carriage, and as the Brougham’s driver tried to stop, the carriage-pole broke, and he lost control of the horses.

William Drake was passing by and saw what happened so, along with a policeman, ran over to stop the frightened horses, therefore, saving the carriage occupants from serious injury. Drake was kicked on the knee by one of the animals, and this relatively minor injury led to blood poisoning, and he died a few days later.

A representative of Mademoiselle Tietjens assured the inquest into his death that she would amply care for his dependents.

Elizabeth Coghlam

Elizabeth Coghlam (1878–1902) was lighting a paraffin lamp on the mantelpiece in a room on the ground floor of her residence when she accidentally knocked the lamp against the wall and broke the glass container. The lamp burst into flames and set her clothes alight.

She dashed out into her yard as there were children sleeping upstairs. Neighbours ran to her aid and extinguished the fire, but she was badly burned. She died in hospital from her injuries.

Despite what is stated on her memorial plaque about Elizabeth dying saving her family and house, the children whose lives Elizabeth Coghlam’s brave act almost certainly saved were not her children. She was a domestic servant, and they were the children of the Brien family whom she worked for.

Other tragic tales include the 23-year-old doctor William Freer Lucas MRCS LLD (1870–1893). While he was administering chloroform during a tracheotomy operation on a child with diphtheria at Middlesex Hospital, the patient coughed into his face. Lucas nonetheless proceeded with the operation. Four days later, he too had diphtheria which killed him within ten days.

And Thomas Simpson who died of exhaustion after saving many lives from the breaking ice at Highgate Ponds on 25 January 1885. Thomas was a 50-year-old farm labourer who worked for the farmer who rented the Highgate pond fields. There were a couple of hundred people on the ice when it cracked yet he did his best to rescue skaters before he succumbed to the icy water. He was dragged out but died soon afterwards.

There are so many fascinating and devastating stories behind the names on the plaques. You can see some excellent guides on the London Walking Tours website and Caroline’s Miscellany. And the full stories about the lives and deaths of every person commemorated on the Watts Memorial are told in Heroes of Postman’s Park: Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London published in 2015.

Your Visit

Postman’s Park is no longer only used by mail workers as it’s popular with City workers at lunchtime and tourists during the rest of the day. Allow yourself plenty of time to reflect as it’s hard not to be moved when you read the tablets on the memorial and think about the terrible tragedies that are being remembered.

Address:

King Edward Street/Aldersgate Street entrances

London

EC1A 4EU

City of London Postman’s Park – London’s Special Memorial to Everyday Heroes — Londontopia — The Website for People Who Love London

Source: Londontopia

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий