The Netherlands and Japan have a long and interesting history together, determined by commerce, trade and war. Here’s a glimpse into this 400-year old history.

Japan, for most of its history, was a relatively isolated country, and whoever dared to invade had to put up with a civilization that was not going to give in easily (we’re looking at you, Mongolians). Yet one day, the Japanese made contact with European civilization, through none other than the sea-faring, spice-stealing, brood-eating Dutch. The Portuguese had made contact with them beforehand, but it is their relationship with the Dutch that proved to be the enduring one.

First contact

The first ship to arrive in Japan from the Netherlands came from Rotterdam, arriving on April 19, 1600. It departed two years beforehand, in 1598, alongside four more ships, three of them being sunk on the way.

The ship that did make it, affectionately called Liefde, lay anchor in the port of Sashifu. The strange-looking ship attracted the attention of the Japanese, especially their military leader (referred to as Shogun) Tokugawa Ieyasu. And what was there not to love? The ship had big cannons, fire arrows and many rifles, just ripe for the taking. And so, everything was taken, and two men from the ship were taken to interrogation. They were Englishman William Adams and Dutchie Jan Joosten van Lodensteyn. The interrogation occurred with the help of a Portuguese translator, yet their witty remarks gained them the liking of the Shogun, who invited them to court so that they may teach their various skills, from cartography to war to ship-building.

The two outsiders quickly gained popularity, and were given lands, titles, and settled down with local women. This laid down the foundation of the relationship between the two countries. The Shogun disliked the Portuguese, which came by not only with trade but also with pesky missionaries who went around spreading the gospel of Jesus, which turned out to be a very unpopular move with the Shogun. As such, the Dutch, with their rational Protestant values, who only wanted to do some good ole’ trading, proved to be a much more appropriate option as a long-term trading partner.

A match made in the seas

The Shogun bestowed on the Dutch a trading permit, which was good news, as the Dutch had recently founded, in 1602, the infamous VOC, the Dutch East India Company. This gave the newly-founded company a new foreign trading partner to conduct commerce with. The VOC managed to obtain a permit to trade with all the shipping ports of Japan, and opened the first trading post in Hirado, in 1609.

This early period of trade was not very profitable for the Dutch as they did not yet have many of the VOC trading posts that they would later establish. Competition with the Portuguese also meant that conflict was on the horizon. The Shogun was not happy with the fighting between these two foreign powers, and started to gradually restrict access and trade. The biggest issue that the military leader had was, however, with Christianity.

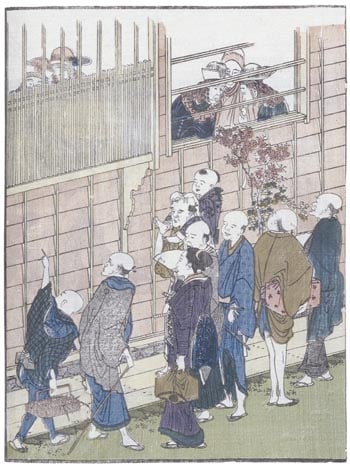

The Japanese decided to build an island, called Dejima, for the Portuguese , in order to limit their access to the country. They did not last long there, and the Portuguese were kicked out of the country out of the suspicion that they supported Christian rebels during the Shimabara revolt. The Dutch were moved in Dejima after committing an honest mistake: they built a stone warehouse, and inscribed the date of its foundation “Anno 1640”. As it was established that Christianity was not really popular with the Japanese, writing the year since the birth of Jesus turned out to cause quite some anger with the Shogun, and thus the Dutch were restricted to trade only from Dejima, starting a new chapter in their trading history.

Western knowledge in Japan

For the subsequent 200 years, between 1641 and 1853, the Dutch were the only Western power allowed to trade with Japan, and thus, they became the gate to the outside world for the Japanese, especially through the VOC. Western science spread to Japan through the port in Dejima, with the term Rangaku (Dutch learning) being used to describe this phenomena.

In its early stages, the process developed quite slowly. Every year, the Dutch would make a visit to the Shogun, bringing with them world news and different kinds of novelties as gifts. Eventually, the Dutch were allowed to conduct private trade in Dejima, leading to a flourishing market, which highly benefited employees of the VOC.

After the opening of a surgeon’s post on the island, high-ranking Japanese officials would come for treatment when their own local doctors failed. A well-known foreign doctor at the time was German-born Caspar Schamberger, who brought with him knowledge of treatments, medicine and medical books.

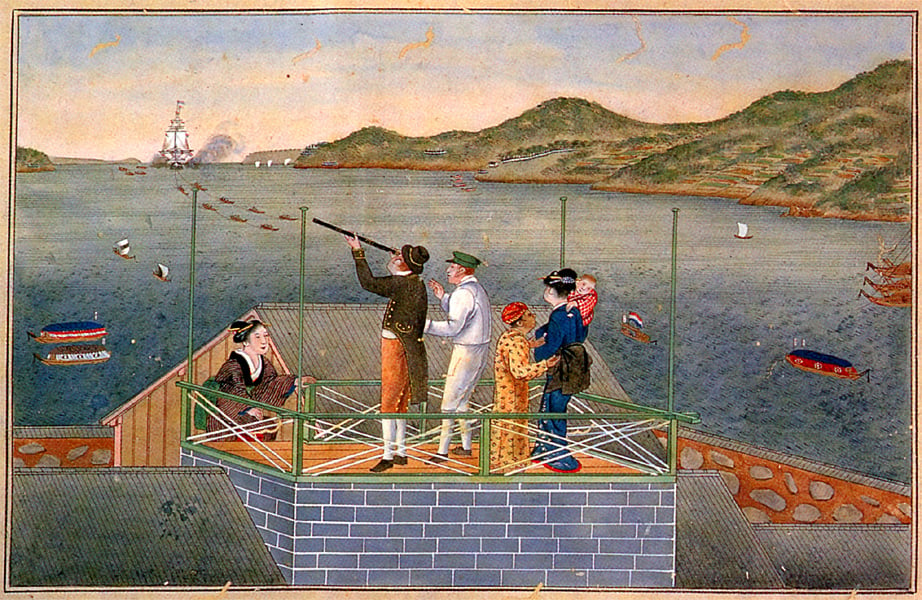

The Japanese elite sought not only treatment, but ordered through the Dutch all sorts of novelties, ranging from microscopes, oil paintings, telescopes, maps and even animals, such as donkeys and birds.

Through the VOC, the Dutch brought many more academics to Dejima, another famous figure being Philipp Franz von Siebold, who was a physician. He managed to open a medical school near Nagasaki, and further developed medical knowledge and treatments in the area. He also made a child with a Japanese woman, and in true European fashion, stole tea plants from Japan and smuggled them to Batavia, the then capital of the Dutch East Indies. He also sent shipments of Japanese cultural and botanical artifacts back to Europe, and on a visit to the Shogun, he illegally received maps of Japan from a member of the Court. The authorities caught on to this, and he was exiled from Japan, leaving behind his lover and his daughter. He eventually settled in Leiden, and nowadays you can find his entire collection of artifacts brought from Japan in the Sieboldhuis in Leiden.

Knock knock, it’s the United States and modernity!

Japan had managed, compared to most of its nearby neighbors, to successfully navigate upholding its culture and traditions, while also maintaining some sort of contact with the outside world through the Dutch and the VOC. It all changed on one faithful day in July 1853.

Ah yes, the United States arrived (we’ve heard this story many times before). Mind you, they were not looking for oil. They were just looking for some trade deals. Aggressive trade deals, but still trade deals. Arriving with battleships in the Tokyo bay, they forced the Japanese to open up the country and allow foreign trade with multiple countries.

This was somewhat bad news for the Dutch, as they lost their exclusive friendship with Japan. But like two old childhood friends who get separated by adulthood and responsibilities do, they still maintained contact, probably through the telegraph.

Japan rapidly modernized in the next 50 years, turning from a feudal society to a full fledged 19th Century Western Democracy. What we mean by that is that it had an appetite to conquer everything around it, like true Europeans (more on that later). The Japanese invited the Dutch to do some classic Dutch engineering, helping with constructing floodgates in areas prone to flooding. An honorable mention of Dutch engineers is G.A Escher, the father of famous Dutch artist M.C Escher, as well as Johannis de Rijke, who did such a darn good job that he became Vice-Minister of Japan. They also sent some of their Japanese scholars to the Netherlands on Erasmus exchange. They also finally formalized their long-friendship, by opening a Dutch consulate in Yokohama in 1859.

A nasty divorce – World War 2

As mentioned before, Japan was very inspired by Western ideas of conquest, and wanted to try it out. We won’t go in details of the many atrocities Japan committed before and during the war, as that is an article for JapanReview to write. Japan was essentially trying to conquest the entire Far East, and guess what land happened to be in the area. Yes, Indonesia. Which also happened to be a Dutch colony. Not one to forego ambitions over friends, the Japanese invaded Indonesia in 1942, and maintained control over the region until the war ended in 1945.

Initially, the Dutch elite ruling the country expected to be allowed to maintain their positions of power. Much to their surprise, they were sent to detention camps, while the Japanese Army started to train local Indonesians, inspiring in them nationalist ideas. This proved to be crucial in the process of Indonesian independence, as it upset the established colonial order. By 1949, the Dutch had no choice but to accept Indonesian sovereignty (not before a bitter conflict that lasted almost 5 years).

The War proved to be the biggest break in Dutch-Japanese relations, and it took some time for them to reach again a level of normality.

Post-war relations

The Dutch no longer had a special place in Japan, and the war made things even more sour. Yet in the decades following the war, the countries started to get slowly close again.

One of the most notable events is the opening of “Holland Village” close to Nagasaki in 1983. A recreation of an actual Dutch village, the project turned out be such a success that it subsequently got extended to “Huis ten Bosch”, opened in 1993.

There’s everything you’d expect in this village. There’s windmills, wooden clogs, Gouda cheese. There’s even a recreation of the Liefde ship, the first one to arrive in Japan 400 years ago. And so, the relationship between these two countries has reached full circle.

Have you ever been to Japan, and if so, did you feel the mark of the relations between these two countries? Let us know in the comments!

Feature Image: Kawahara Keiga/ MIT Visualizing Cultures/ Wikimedia Commons

The post Van hier tot Tokio: A history of Dutch-Japanese relations appeared first on DutchReview.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий