There is an adage among miners: if it can't be grown, it must be mined.

Almost everything we use relies on mining. Phones and computers contain elements like aluminum, nickel, and lithium. Plastic is made from petroleum products extracted from fossil fuels in the ground. Even your toothpaste is chock full of mined materials.

The growing human population places an increasing demand on the non-renewable resources that come from Earth's crust. Technological advances and the search for renewable energy sources could exacerbate the situation. As our terrestrial mineral resources diminish, governments, researchers, and corporations have proposed searching for resources in a new location: thousands of meters beneath the surface of the ocean.

In the 1970s, researchers began exploring the potential of extracting minerals from the seafloor after discovering fields of potato-sized polymetallic nodules and massive mineral-spewing underwater volcanoes, called hydrothermal vents. A seemingly endless supply of metal ores resided in the deep ocean and promised a wealth of resources. We just had to find a way to extract and transport them to the surface.

The United States, France, Germany, and the Soviet Union funded nearly 200 research cruises to investigate mineral resources around the world. Lockheed and Ocean Minerals Co. inspired hope in ocean mining’s feasibility when they announced their automated mining system was capable of operating at depths of 6,000 meters. However, the development and testing of their mining system between 1976 and 1978 was later revealed to be a cover for a United States Central Intelligence Agency mission to recover sunken Soviet submarines. Despite investments equating to over $650 million USD, exploration and technological developments ultimately proved impractical and unprofitable. By 1982, enthusiasm dwindled and the United States, France, and Germany all ended deep-sea mineral exploration programs.

50 years later, improved technology and heightened demand for precious natural resources — like the rare earth metals needed to construct longer-lasting, energy-efficient batteries — have led to a resurgent interest in exploiting deep-sea mineral deposits. Many scientists, however, are worried that mining will irreversibly damage fragile deep-sea habitats and have unforeseen consequences on other ocean environments.

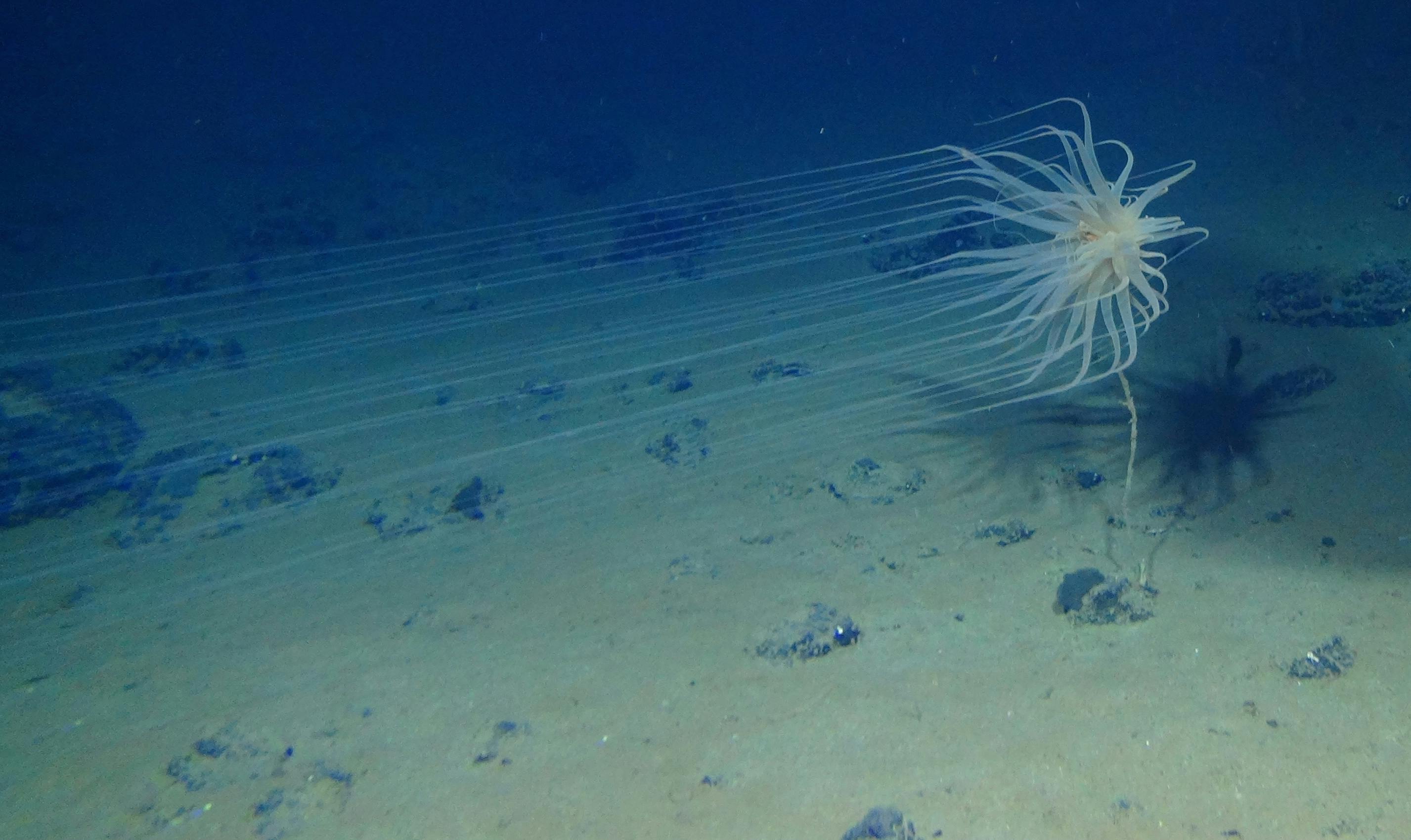

Newly-discovered cnidarian species (Relicanthus sp.) found in the Clarion Clipperton Zone at 4,100 m depth

NOAA

Mining 3000 leagues under the sea

Deep-sea mining will mimic mining operations on land, with one large caveat: everything must take place under crushing pressures and near-freezing waters. On top of that, the deposits in question (polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulfides, and cobalt-rich crusts) predominantly occur at depths between 400 and 6,000 meters below sea level, prohibiting the use of manned vehicles. Instead, mining operations will be entirely controlled from a support ship on the surface. Fiber optic cables running from the ship to the seafloor will power and control mining vehicles that look like a supervillain’s tool for world domination with instruments for crushing, scraping, and suctioning sediment and ore. After the ore has been extracted from the seafloor, a slurry of minerals, sediment, and seawater must be mechanically pumped back to the support ship where the desired metals will be separated from the rest of the slurry. Any unwanted water and materials — called "tailings" — will be discarded back into the ocean.

From seafloor extraction to surface processing, scientists worry about the damages deep-sea mining operations will inflict on marine environments. Mining will remove surface sediments and chunks of the seafloor, uprooting organisms living there. Vehicles extracting minerals will also generate large sediment plumes that can travel well beyond the mining site, smothering animals in their wake. Pumps transporting minerals to the surface will create noise that will likely be able to travel hundreds of kilometers in every direction without dissipating, disrupting the behaviors and communication of animals, like whales, that are accustomed to a quiet oceanic environment at such depths. After ore processing, the release of tailings could further pollute waters hundreds to thousands of meters away from the actual seabed mining operations depending on where they are released back into the water.

There’s more. Pollution from tailings in midwater habitats could throw off the balance of food webs by changing the way food sinks from the surface down to animals in the food-limited deep sea. Mining might also release toxic chemicals and heavy metals into the environment at dangerous levels. Because deep-sea animals serve as a primary food source for many endangered marine mammals and commercially important fishes, like tunas, those toxins could make their way up the food chain and cause unintended health issues in marine animals and humans.

%20mining%20impacts.jpg?auto=compress%2Cformat)

Likely mineral extraction methods and some of the possible sources of disturbance to target and surrounding ecosystem

Miller et al., 2018 / Frontiers in Marine Science. CC

Scientists cannot yet predict the extent or severity of these environmental impacts, particularly when there is no working model of a commercial mining operation. Since most of the mineral deposits sit within international waters, their exploitation is regulated by an international governing body called the International Seabed Authority, or ISA, composed of 168 member states. (The United States is not a member — despite resounding support from military officials, oil and gas companies, and both Democrat and Republican legislatures — due to concerns from a small, but vocal, conservative base that worries that the ISA and the Law of the Sea would threaten U.S. security, sovereignty, and economic interests.)

The ISA has drafted regulations for the exploration of deep-sea mineral deposits and has already issued 30 contracts allowing governments and independent companies to collect baseline data on mineral resources, test mining procedures, and conduct environmental impact assessments in locations within the Indian, South Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans. Currently, ISA has prohibited mineral extraction while it drafts the Mining Code — a set of regulations that will ultimately determine the fate of future mining endeavors. Commercial mining operations could being as soon as the Mining Code is finalized, which ISA suggests could happen by the end of 2020.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law Of the Sea, all mineral deposits within international waters are considered to be the "common heritage of mankind" and ISA is therefore responsible for ensuring the Mining Code includes regulations and guidance to ensure "the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed related activities.» But we’re still years away from understanding deep-sea ecosystems and organisms well enough to develop and implement regulations that meaningfully reduce mining's environmental impacts.

Mysteries of the deep

The waters of the deep ocean (below 200 m deep) make up over 90% of our planet, but deep-sea biology is a nascent field that has historically been hampered by our inability to conduct basic experiments and observations. Recent explorations have uncovered remarkable aspects about the creatures living in the deep oceans and how they rely on and fuel shallow-water ecosystems, but we still lack a critical understanding of the basic biology, ecology, and recovery potential of these creatures and ecosystems.

What we do know is that the ecosystems targeted by mining operations — including hydrothermal vents, seamounts, and nodule fields in abyssal plains — all create unique oases of life within otherwise homogenous underwater deserts.

Many species within these ecosystems are incapable of surviving anywhere else on Earth, such as communities that rely on the boiling hot (up to 400° C, 750° F), toxic effluent emitted from active hydrothermal vents. Many of the deep-sea habitats harbor an incredible diversity of life, even comparable to that of the Great Barrier Reef. And scientists continually discover new species in these habitats, many of which can only be found at a single vent or seamount. But the creatures inhabiting the deep sea grow slowly (some only growing 1 millimeter each year) and can live for hundreds to thousands of years, making their capacity to recover from mining operations particularly worrisome.

Deep-sea fishes like this roughy can live for over 100 years and rely on hard bottoms like those found at seamounts

NOAA

Our best predictions of the long-term environmental impacts of mining activities come from a few small scale tests. Experiments simulating polymetallic nodule mining in both the Peru Basin and the Clarion-Clipperton Zone within the central Pacific suggest that mining operations will devastate mining sites for years. Even 26 years later, scientists saw little evidence of ecosystem recovery in these sites: not even microbes had made a resurgence.

But these experiments pale in comparison to the eventual scale of commercial mining operations, which are expected to span 10 to 100 times the area surveyed in the Peru Basin and cause significantly more damage to the seafloor than simulated in any trial to date. Ecosystems will simply suffer irreversible alterations to their health and take hundreds or thousands of years to recover from the habitat destruction caused by mining.

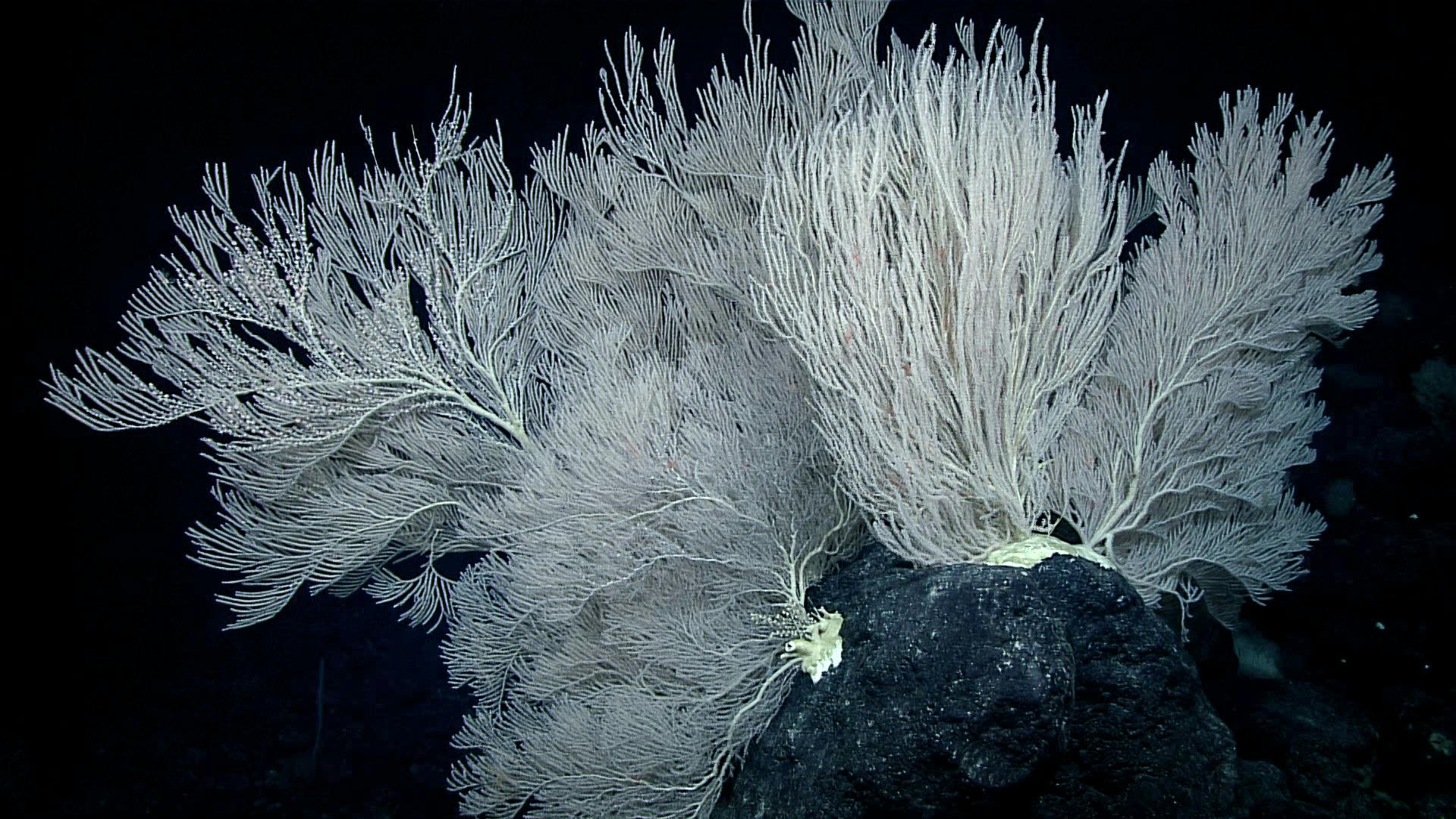

A garden of pink corals on a seamount at 1,800 m

NOAA

Other scientists worry that this level of destruction will inevitably cause a loss to biodiversity and could entirely wipe out species endemic to a single mining site. Scientists also predict that mining impacts will spill-over into surrounding seafloor and midwater habitats, but the extent and outcomes of environmental impacts remain a mystery since mining exploration has largely ignored other oceanic ecosystems. Due to the inherent connectivity between the deep-sea and shallow water systems, devastation from deep-sea mining could even ripple through the rest of the ocean, with unforeseen repercussions on the health of the animals living in, and relying on, our seas.

Minimizing Harm

ISA seems to have accepted the inevitability of environmental damages from deep-sea mining and plans to focus on minimizing harm and restoring ecosystems after mining damage occurs. By doing so, ISA may fail to uphold its responsibility to protect the fragile deep-sea habitats from harmful mining activities. Scientists have expressed concerns over the recommendations within the latest strategic plan that provide only non-binding guidelines with little legal backing to ensure adherence from contractors. Some also find flaws in the plan's apparent reliance on restoring damaged habitats after mining — efforts which prove costly and often unsuccessful even in the shallow water habitats (like coral reefs and salt marshes) that we understand far better than any deep-sea ecosystem.

At this point, scientists have no blueprint for habitat restoration in any areas mining will impact, nor will they within the foreseeable future. Ultimately, the restoration of deep-sea habitats is an unconvincing solution. This approach received criticism from several member nations concerned that the plan "could be read as if the Authority's aim is to develop Exploitation Regulations that encourage deep-sea mining" when ISA's responsibility is to ensure the pursuit of deep-sea mining only if it is in the best interest of all humankind.

With so many unanswered questions about the environmental impacts of deep-sea mining, a cautious approach seems warranted. Yet, plans for deep-sea mineral exploitation appear to be rolling forward at full steam. A Belgian company, Global Sea Mineral Resources, recently finished test driving a vehicle intended for mining polymetallic nodules, and companies like Blue Nodules and Deep Green are investing big in mining equipment they claim will reduce environmental impacts — the efficacy of these designs has yet to be tested in deep-sea environments.

Ashley Marranzino studies

Marine Biology

at

University of Rhode Island

.

Source: massivesci.com

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий