10 million years ago, the Andes Mountains rose up, reversed the Amazon River's course, and set the stage for the world’s largest rainforest. Ever since, the mountains have continued to build the Amazon rainforest using rivers as their tools.

Within their tumultuous waters, Andean rivers harbor a process that shapes the lives of millions: transforming mountain rubble into the building blocks of ecosystems. This process is intricately tied to their steepness, volatility, and penchant for disastrous landslides, which is partly why their essential role has long gone unappreciated.

This is one of the conclusions of a recent review in the journal Science by an international team of river researchers, led by Andrea Encalada from Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador. Their research highlights the rivers in the Andes and tropical mountain ranges worldwide and their outsized role in shaping tropical lowlands. They argue that this important biological and geological role has several key attributes: the extreme gradient of climates they pass through, the dynamic environment created by their volatile flows, and their extraordinary ability to export nutrients and sediments downstream.

An isolated rainstorm pummels small Andean river valleys in Ecuador

Jeremy Snyder

Although most people think of rivers in geographical terms, or as mere features on a map like lakes or hills or highways, it is arguably more useful to think of them as a process: a collection of ongoing interactions between water and land. A river is less a noun than a verb.

As rivers move downhill, they connect the tops of mountains to the bottoms of the ocean. They act as conduits for water, rock, and organic matter being ushered seaward by gravity. Along the way, they help supply inhabitants of the landscapes they flow through with everything from the food they eat to the ground beneath their feet.

The core of this process is weathering and erosion. The flow of water drives a complex suite of reactions that break down bedrock into soils and bio-available minerals. Where inclines create moving currents, rivers move rocks and soil downstream and break them down further. These chemical and physical processes liberate and transport mineral nutrients like the phosphorus, calcium, iron, zinc and potassium that virtually all of Earth's organisms need to survive. The river also sweeps up decaying organisms, plant matter, and detritus along its banks — essential carbon and nitrogen to fertilize downstream plants and nurture the microorganisms that many other things eat. Encalada explains that these nutrients are "critical for the productivity of the downstream ecosystems. Phytoplankton and the entire food chain depend on these nutrients, and they are also important for the productivity of nutrient-limited forests that need that input for growth."

A kayaker paddles the Piatua River in Ecuador, among boulders brought down from the Andes

Jeremy Snyder

In steep, still-growing ranges like the Andes, intense rains create landslides and sudden floods which tear up stream beds and move massive quantities of sediment and woody debris downstream. In spite of their often disastrous impacts on humans, these surges do a lot of heavy lifting. «[Andean rivers] carry out an enormous amount of river processes, disproportionate to their volume and length,» says Elizabeth Anderson, co-author on the Science paper and an aquatic ecologist at Florida International University. The material they move plays an essential role downstream. "So much of the richness of the lowland Amazon is linked to these rivers moving organic matter, water, sediments, and nutrients out of the Andes,» says Anderson.

Today, broken down Andean rock accounts for 93 percent of the roughly 1 billion tons of sediment carried by the Amazon River each year, and the vast majority of its nutrients. As the muddy torrents exit the mountains, they run out of momentum on the flat floodplain and begin to drop their load. The accumulating material raises the river bed and slowly nudges the water into new terrain, building up the landscape in its wake. The modern Amazon rainforest resides on ground made up of ancient mountainsides, scrounging minerals from sediments on their journey to the sea.

And yet, despite their roles as exceptional ecosystems and critical conduits, Andean rivers are being increasingly targeted for dams and developments which disrupt the very traits that make them valuable. When the momentum that carries sediments and nutrients is co-opted to spin hydropower turbines, that critical cargo is left to settle to the bottom of a reservoir.

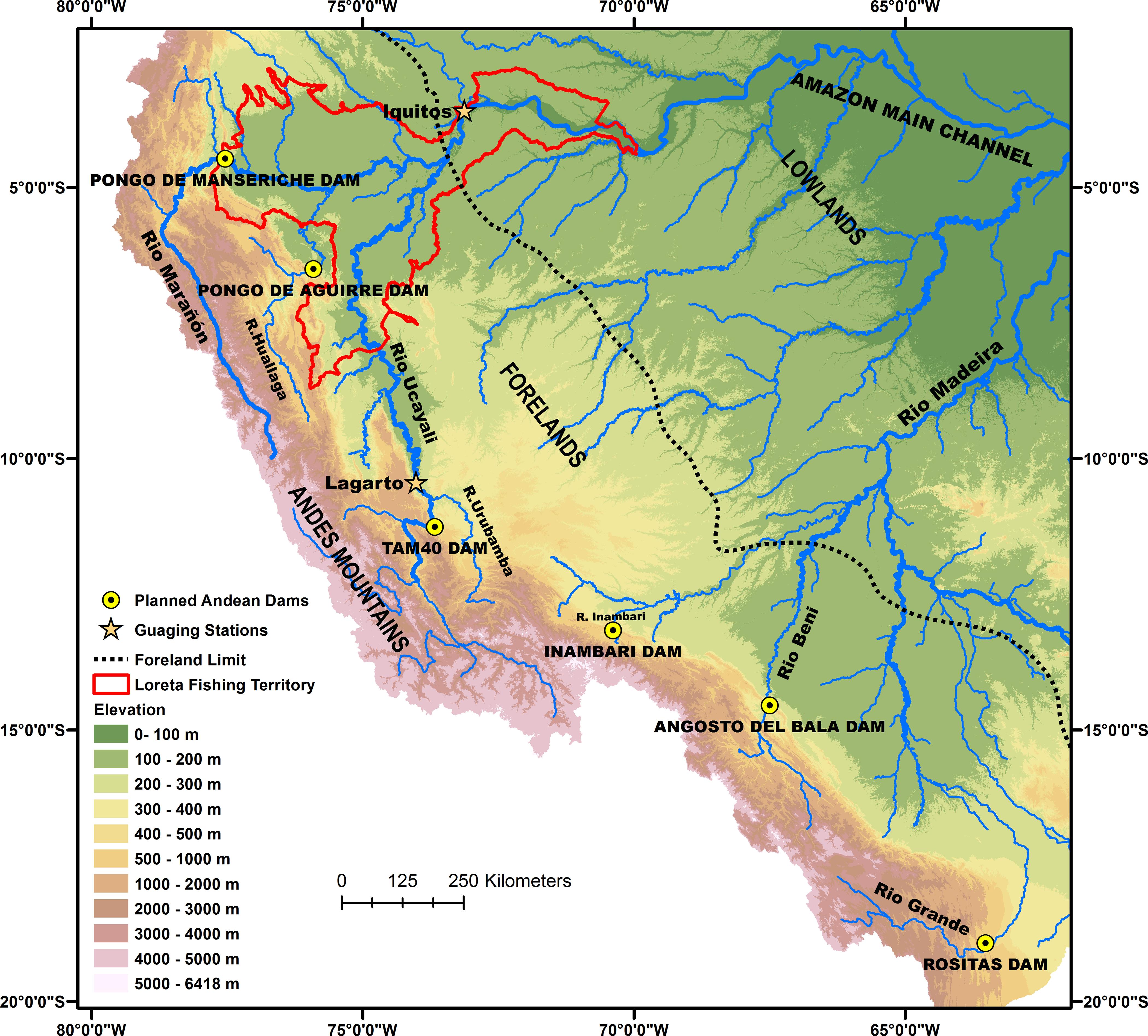

A map of planned dam projects in the Andean Amazon

Forsberg et al PLoS One 2017

Through disruptions like these, the system that nurtures the Amazon is at risk of being broken. Six major dams planned on the Andean reaches of major rivers like the Marañón, Ucayali, and Huallaga in Peru would block an estimated 64 percent of all sediments that the Amazon region normally receives, with accompanying precipitous losses in phosphorus and nitrogen.

Such losses would have very real consequences for people living downstream.

Andean sediments make up the river banks and islands that people live on throughout the Amazon, and dictate how rivers meander across landscapes and behave across seasons. Even as far as the Atlantic, thousands of miles to the east, Andean sediments supply sands to beaches and mangroves along the coast. When the steady deposition is blocked, these dependent regions will begin to waste away, just as they already have in other dammed and leveed rivers like the Mississippi.

The reservoir of the Coca Codo Sinclair Dam in Ecuador, filled with sediments that normally would have been carried to the Amazon. The dam is now threatened by runaway erosion downstream

Jeremy Snyder

The blocked water will be missed as well. Each rainy season, monsoon rains in the Andean highlands lead to swollen rivers that can rise 30 to 40 feet from their dry season level. As water and sediments flood over the banks, they bring a nourishing pulse to thousands of square miles of rainforest. Fish swarm into the flooded forests to gorge on fallen fruits and reproduce, dispersing seeds and renewing the richness of Amazonian fisheries so significantly that the biggest fish yields consistently follow the largest floods. Hydropower dams often cripple this seasonal ebb and flow in favor of more consistent output, which would drown lower floodplains under a permanent flood and strand the upper banks in a perpetual drought.

Freshwater fisheries act as one of the primary sources of income and protein for the 30 million plus inhabitants of the Amazon Basin. These natural safety nets for indigenous people and rural poor owe much of their richness to the flood pulses and nutrients coming down from the Andes. Consequently, they too are expected to suffer from the planned disruptions.

A giant catfish from the fisheries of the Amazon river being carried up to market in Iquitos, Peru

Jeremy Snyder

The paper published by Encalada and her colleagues is one of the first to highlight mountain rivers’ global importance. This is in part because they have long been thought of as mere connectors between better-studied ecosystems, rather than distinct systems in their own right. It is also because they are often steep, remote, and difficult to study. As Anderson says: "Sampling those rivers is no joke."

The rush to dam Andean rivers is a sign that few people understand the extent of services they provide in their natural state. But with human developments encroaching on mountain rivers everywhere, such knowledge gaps are becoming dangerous.

Dams in the Andean Amazon are already having downstream effects, most recently in Ecuador, where sediment-deprived water from the country’s largest dam has been implicated in undercutting a 390 foot waterfall earlier this year. Beyond destroying a landmark, it kicked off an ongoing disaster as the river excavates a new canyon to re-level its gradient, destroying highways, rupturing oil pipelines, and threatening the dam itself in the process.

Mountain rivers act as important conduits that connect the Andes to the Amazon floodplain

Jeremy Snyder

The Andean Amazon has long been one of the few remaining river systems that is mostly un-dammed, but that is changing fast. As of 2017, 142 hydropower projects existed in the Andean Amazon, and another 161 had been proposed or were under construction. Even as scientific consensus is building that large hydropower dams cause more harm than good, dam development in the region is poised to proceed at a breakneck pace.

Andean rivers have long been ignored because few people think of them in terms of processes they perform. Anderson concludes that if we forge ahead without proper understanding, we may find out the hard way just how much depends on the river process. "Each dam that goes up is like a natural experiment on river processes and connectivity, and what happens when you cut them off," says Anderson. "It's not an experiment we would like to be running, but the sad reality is that we are already seeing the effects."

Jeremy Snyder studies

River Geology and Photojournalism

at

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories

.

Source: massivesci.com

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий