In 1948, just three years after the end of World War II, a leading Nazi war criminal managed to escape from a prison in Linz, Austria.

Franz Stangl, a former SS-Hauptsturmführer and commander of the Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps, was responsible for the deaths of almost 1 million Jews. Via Graz, Merano and Florence, he made his way to Rome and — most importantly for him — to the Vatican.

In Rome, Bishop Alois Hudal, a fellow Austrian, greeted him with the words: «You must be Franz Stangl — I’ve been expecting you.» He then handed Stangl forged documents that allowed the Nazi war criminal to travel to Syria, where his family eventually joined him. In 1951, the Stangl family emigrated to Brazil. The man who perfected mass murder in the concentration camps spent years assembling cars at a Volkswagen plant near Sao Paulo.

Franz Stangl is one of thousands of Nazis and collaborators who, with the help of the Catholic Church, escaped Europve via routes called «ratlines» — some of which ran from Innsbruck over the Alps to Merano or Bolzano in South Tyrol, then to Rome and from there to the Italian port city of Genoa.

Stangl chose a detour via Syria, but the majority of Nazis boarded ships headed directly to South America — mainly to Argentina, the country Holocaust survivor and writer Simon Wiesenthal named the Nazis’ «Cape of Last Hope.» Argentina was that last country to declare war on Nazi Germany.

Read more: The student who hunted Nazi judges in postwar Germany

Spontaneous cooperation?

«The ratlines were not a thoroughly structured system, but consisted of many individual components,» said Daniel Stahl, a historian at the Department of Modern and Contemporary History at Jena’s Friedrich Schiller University. «It was more of a spontaneous cooperation of different institutions that gradually established itself after World War II.»

Some 90% of Nazi perpetrators who escaped Europe are thought to have fled across the Alps to Italy — that was the first loophole.

Their first stop was in the South Tyrol region of northern Italy: the monastery of the Teutonic Order in Merano, the Capuchin monastery near Bressanone or the Franciscan monastery near Bolzano. The war criminals would often hide out in monasteries — these ratlines are also known as the «monastery route» — for years, collecting money to continue their escape overseas. Sometimes, the Nazis were accommodated right next to their former victims, Jews headed to Israel.

Read more: Nazi officer’s sons trace clues in wartime letter in search of his fate

Rome was the next stop. The Nazis who had a letter from the Catholic Church confirming their identity were handed a passport by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which issued about 120,000 papers until 1951 — a mere formality.

«The story goes that even before the end of the war, there was a clearly thought-out and elaborate plan for Nazi escapees,» Stahl said. «That is wrong, even the likes of Franz Stangl first wandered around Rome without knowing what to do next.» Information was passed on word of mouth.

A name that regularly crops up is Alois Hudal. The Austrian bishop had clearly positioned himself as a Nazi sympathizer during Nazi rule, and later he said many of those persecuted were «completely blameless» and that he «snatched them from their tormentors with false identity papers.»

Read more: The tormentor of the Krakow ghetto: The secret life of Horst Pilarzik

Popular clandestine route

«It would have been much more difficult for Stangl and the others to flee» if the Catholic Church had not protected many Nazis, Stahl said.

The list of infamous Nazis who used the ratlines is long.

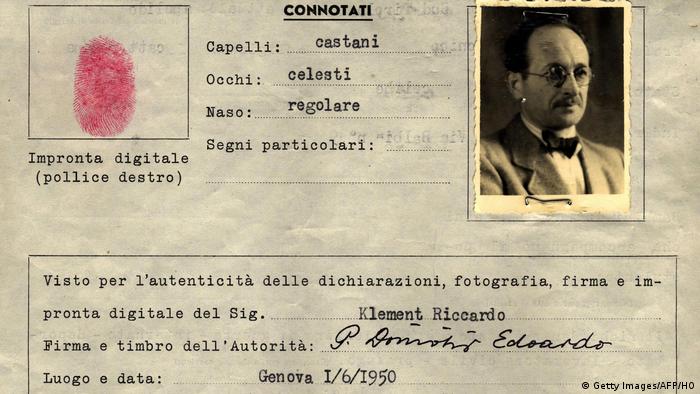

Adolf Eichmann

Using the name Riccardo Klement, the man who organized the Holocaust fled from Bolzano to Argentina in 1950. His family later joined him. Grateful for the Vatican’s help in his escape, Eichmann converted to Catholicism. He worked as an electrician at a Daimler-Benz truck factory. In 1960, he was kidnapped by Mossad, Israel’s secret service, and brought to trial in Israel. He was executed in the night from May 31 to June 1, 1962.

Josef Mengele

The sadistic Auschwitz concentration camp doctor fled to South Tyrol in 1949, where supporters provided him with a new passport. His new name was Helmut Gregor, 38, a Catholic and a mechanic, born in the South Tyrolean village of Tramin. The detail of his birth in South Tyrol would prove the most important condition for leaving the country. As a South Tyrolean citizen, he was considered an ethnic German as well as stateless, and therefore entitled to an ICRC passport. Mengele lived in Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil, where he suffered a stroke while swimming and drowned on February 7, 1979.

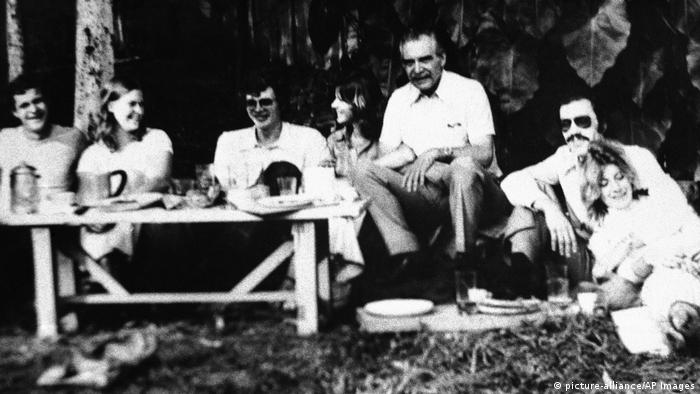

The man believed to be Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele, third from right, during a picnic with friends in Sao Paulo, Brazil

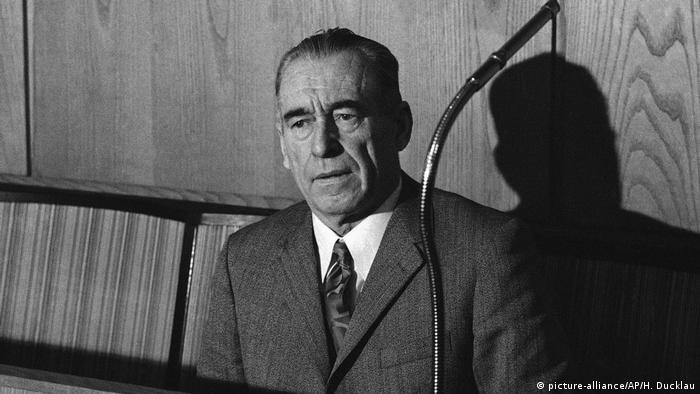

Klaus Barbie

Known as the «Butcher of Lyon,» the French city’s former Gestapo chief set off for South America as Klaus Altmann of Romania. With the help of the CIA, Barbie obtained a visa for Bolivia in 1951 and continued to receive orders from the US foreign intelligence service and the German Federal Intelligence Service (BND). His whereabouts became known to the public in 1970. Bolivia extradited him to France in 1983. He received a life sentence and died of cancer in prison on September 25, 1991.

Erich Priebke

The SS captain was partly responsible for the massacre of 335 civilians in a reprisal killing in the Ardeatine Caves near Rome in 1944. He fled from Latvia to Bariloche in Argentina under the pseudonym Otto Pape. Argentinian authorities extradited him to Rome in 1995. Three years later, he was sentenced to life in prison and died under house arrest on October 11, 2013.

Walther Rauff

Rauff invented mobile gas chambers, in which exhaust fumes were fed directly into the back of redesigned vans. According to his arrest warrant, he was responsible for at least 97,000 murders. In 1949, he fled along the ratline together with his wife and two children, to the Ecuadoran city Quito, then continued on to Chile. West Germany requested his extradition in 1963, but it was rejected as the crimes Rauff was accused of had expired under Chile’s statute of limitations. Rauff became a wealthy food producer and died of a heart attack on May 14, 1984.

Read more: ‘Daddy was a man of honor,’ daughter of Nazi SS officer insists

What did Pope Pius XII know about the ratlines?

Despite all the evidence historians have compiled about the ratlines, one questions still remains unanswered 70 years on: How much did Pope Pius XII know about them?

That’s exactly what church historian Hubert Wolf intends to find out. Together with dozens of colleagues from around the world, he plans to spend the next four months combing through Vatican documents. On March 2, the Holy See will publish the archives from Pius’ tenure for the first time.

«It’s an incredible opportunity to answer several pending questions from the era, and a huge challenge,» the professor of church history at the University of Münster told DW. «We’re talking about 300,000 — 400,000 documents of 1,000 pages each.»

Wolf knows from past experience scrutinizing the archives of the Inquisition, that researchers will spend weeks studying nothing of importance before stumbling across a «treasure trove.»

Read more: Nazi victim files go online in German archive

Hoping for answers

A serious verdict on the contents of the archive will take years, Wolf warns. However, he is still optimistic about gaining meaningful insight into the ratlines. «For example, did the pope issue direct instructions or was it a more general order to help people without papers,» Wolf says. «Or is there concrete evidence that the pope, with encouragement from the CIA, thought: ‘it would be a good idea to send nationalistic people to Latin America because Communists were actively trying to overthrow the continent’.»

Pius XII’s fear of communism is well-documented, and was a point of reference for clergy helping on the ratlines. The justification was that whatever the National Socialists did during the war, at least they fought communism and had to be protected from political persecution. Communism was seen as the greatest threat to the Catholic Church.

«It may transpire that the pope knew nothing of any concrete help and that some people ruthlessly exploited that. Or Pius knew all about it, and turned a blind eye,» Wolf told DW. So the all-important question that the opening of the archives must answer is: «Was the pope manipulated or did he know about people like Josef Mengele? That would be a whole new dimension.»

To read the article in English. Deutsche Welle Europe

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий