If you wander away from the centre of Geneva along the Rhône, past the big hotels and the Bâtiment des Forces Motrices, you might stumble upon Andersen Genève’s atelier. Given the slightly out-of-the-way location, it’s probably unlikely, but if you do, you may be lucky enough to find Svend Andersen working at his bench.

Mr Andersen is something of a legendary figure in the world of independent watchmaking, having co-founded the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants* (AHCI) in 1985 with Vincent Calabrese. Its aims were (and still remain) to promote handmade timepieces, attract the world’s most creative independents and support young clock- and watchmakers**.

Svend Andersen was also at the head of his own brand for four decades until he took (semi-)retirement in March 2015. I first met his replacement, Pierre-Alexandre Aeschlimann at SalonQP that year, and then again at an evening organised by a fellow #watchnerd. Pierre-Alexandre brought along a selection of watches that represented the current Andersen Genève collection, including examples of the Montre à Tact, Jour et Nuit, World Time and even some unusual, erotic watches.

Holed up in a conference room deep in the bowels of the Royal Automobile Club on Pall Mall was, perhaps, not an ideal setting to explore the rich history of the brand, nor Svend Andersen’s impact on the world of horology and independent watchmaking. However, Pierre-Alexandre’s sheer exuberance quickly won over everybody around the table, and I have to admit that it was quite fun to see #watchnerds closely examining the goings on of the various eroto-automata.

Watchmaker of the impossible.

For the last four decades, Sven Andersen’s philosophy has been never to say no to a customer. This has lead to some quite extraordinary watches, many of which became models within the Andersen Genève collection, although some remained pièces uniques. During that time, Mr Andersen has also been commissioned to undertake modifications of other watches, and it was upon one of these latter pieces that he was working when we met him in January.

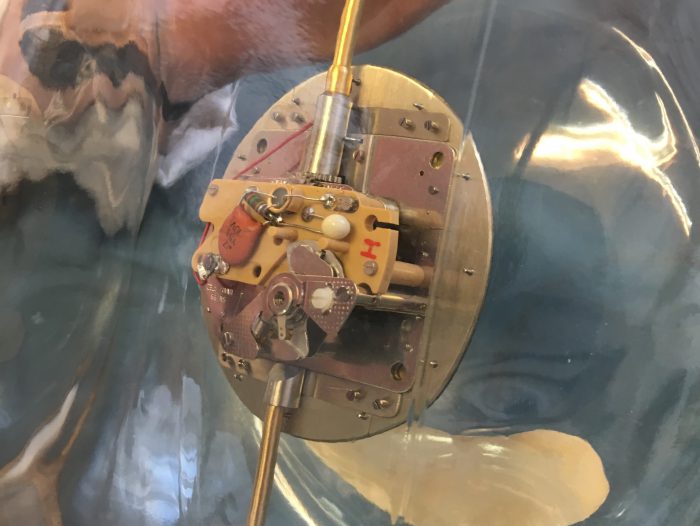

I’d been given Mr Andersen’s mobile number by Pierre-Alexandre so that we might arrange a convenient time to visit. Although officially retired, Mr Andersen spends more than a few hours a week working in the atelier. On the afternoon of our visit, he was servicing a flyback calendar module that a client had asked him to add to a Tiffany & Co-retailed triple date. The module meant a new dial was required, as well as a mid-band to increase the height of the case.

It’s never easy, meeting watchmakers like Mr Andersen. How does one even begin to interview a man who launched an independent watch brand four decades ago and co-founded the AHCI in 1985? Sometimes it’s best just to start at the beginning, and so, after a brief chat about the many talented independent watchmakers who form the membership of the AHCI, I asked him about clocks.

Back in 1969, before his world time watches, erotic dials and secular perpetual calendar, Mr Andersen worked for Gübelin and it was during this period that he created a series of items that managed to take the idea of the “ship in the bottle” and combine it with horology. The production of these Bottle Clocks brought Svend to the attention of Patek Philippe, amongst others, and he soon found a job working in their complications department.

If you’ve not seen one of these “bottle clocks” up close, it can be difficult to comprehend how he managed to do it at all: the dial and movement are in pieces, and were assembled inside the bottle. Of course, with the neck of these bottles being so narrow, Mr Andersen not only had to cut the pieces into relatively small strips, but also to find a way to assemble them in situ. A sample of the tools is shown at bottom left in the photo above.

Turning the bottle over makes it a little easier to see how the pieces fit together, but doesn’t really give an indication as to how these small screws were affixed. The tools that Mr Andersen had to invent just to assemble these Bottle Clocks are works of art in themselves: forceps operated from outside the bottle; screwdrivers with a ninety-degree turn; and long tweezers to hold the screws in place. Of course, these were largely electrical clocks, with the batteries hidden in the stoppers, rather than manually-wound mechanical movements, but they remains items of wonder and so little magic.

Inspired by Breguet.

The modern Andersen Genève collection does not include any clocks, although it does build on the playfulness that can be seen in almost everything that Sven Andersen has designed. The Montre à Tact, for example, is a take on the watches made by Breguet from the late 18th century. In 1795, just as now (perhaps), it was considered rather impolite to look at one’s watch during dinner, or while having a meeting. Where Breguet’s watches were largely tactile in nature, the Andersen Genève version replaces the dial and hands altogether, replacing them with a circular rotating display, visible through a gap in the case between the lugs.

Introducing a revolving display allows the watch to be read at a much lower angle, and usually without moving the wrist at all. Of course, when you surround the movement, you make it impossible to have a normal crown; hence the winder is relegated to the back of the watch. Relegating time to the edge of the case frees up the entire dial, leading to some interesting designs. I particularly liked the aventurine version (below), which is absolutely stunning in natural light.

Perhaps the most unusual (excluding the erotic watches) were the poker-playing dogs – a series of seven or eight scenes, based on the Coolidge paintings. Each of these is unique, hand-painted onto the “dial” by a local miniature artist. While photographing one of these pieces, I noticed that the painter had managed to include the Andersen Genève logo on the cigar band!

I asked Pierre-Alexandre during SalonQP whether it was possible to remove the dial display altogether, so that the only way of telling the time was through the lugs. He showed me some renders he had on his iPhone, and while it’s an interesting look, I think you’d need to be pretty brave to carry it off. There is, however, a new ladies version with a domed, pavé-diamond “dial”, called the Regina. Although I haven’t see this model, it reminds me of some of the cocktail watches from the past, with hidden dials beneath a hinged, jewelled top.

Supporting independent clock- and watchmakers.

Spending time with people in the watch industry is always rewarding, and I’m immensely grateful to Pierre-Alexandre and Mr Andersen for the time that they given me over the past two years. When speaking to watchmakers, I often feel increasingly guilty: I’m not a journalist; I’m not a collector of high-end watches; I’m not even an influencer. I’m just someone who loves horology, in all its many forms, and wants to see it survive and flourish.

Without Mr Andersen I am sure that the world of independent watchmakers would be a lot smaller. The Académie he co-founded continues to play an important part in the support and development of independent watch- and clockmakers, through its work and partners (such as MB&F and FP Journe). If you would like to support the AHCI, while also receiving a few benefits, you may like to consider joining the Circle of Friends.

the #watchnerd

*Dr George Daniels was one of the first members of the AHCI..

** I’d love to do more to support young watchmakers; it’s something I believe is essential to the future of horology and watchmaking. I’m thinking of adding a page to the ‘site that links to young, up-and-coming watch- and clockmakers and their work. I’m also planning a #watchnerd event for next year, to try to give something back to the community. Hopefully, I’ll be able to persuade a few people to get onboard and help out.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий