Almost a decade later, Charles Frodsham & Co quietly announced the launch of their Double Impulse Chronometer, a wristwatch containing a unique escapement that, prima facie, looks remarkably like the original prototype**. However, that surface similarity belies the work undertaken by Frodsham’s over the last thirteen years: while the movement been continuously tested and refined, and many blind alleys and culs de sac have been investigated, the team has also had quite a few other things on their collective plate.

I owe a great deal to Frodsham’s management and staff: as a new member of the Antiquarian Horological Society and occasional visitor to BHI and Worshipful Company of Clockmakers events, Frodshams were always friendly, helpful and encouraging. Whether it was sharing anecdotes over post-AHS dinners, providing additional information about a pocket watch I’d purchased, or showing me around the recent exhibition of clocks from the Belmont collection at Bonhams, they have always supported my nascent #clocknerd and #watchnerd education. But I must admit that I was slightly taken aback when I was invited (along with sister ‘blog, Horologium) to their Bury Street showroom back in January to see their new Double Impulse Chronometer***. It’s at this point, for the sake of transparency, that I should add that there is no financial relationship between me and Frodshams.

The newly refurbished Bury Street showroom is a treasure trove, mapping out the 180-odd years since Charles Frodsham started making pieces under his own name. Clocks, pocket watches and other ephemera are displayed in various cases or against the walls, while the solemn tick and tock of a large turret clock mechanism provides an appropriate soundtrack. The business remains the longest continuously trading firm of chronometer manufacturers in the world, and the Frodsham name is still synonymous with precision timekeeping. It is therefore no surprise that the wristwatch has been named the Double Impulse Chronometer – a nod both to the marine chronometer history of the firm, as well as to its timekeeping abilities.

Sitting down with Philip Whyte and Richard Stenning in January of this year was one of the most remarkable afternoons I’ve had since I began my horological journey. The Chronometer is a watch that has been teased over the past few years, with under-the-cuff hints and occasional views through time-frosted casebacks. But to finally see the finished article was a rather emotional moment. As I looked at the strange, ethereal dial, a mounted photo caught my eye: a carriage clock commissioned by The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers from 2012 shared the same design. How very like them to hide their wristwatch in plain sight.

Richard informed me later that the original inspiration had been taken from a 1900s tourbillon pocket watch in the Frodsham private collection. With its inner railtrack minutes punctuated by sharp triangles for the major markers, it was remarkably and instantly legible. Indeed, it takes the brain a little while to process the fact that both hands are – somewhat unusually – of equal length. However, unlike the original tourbillon, or the more recent carriage clock, the Chronometer’s dial is more sculptural, with raised numerals in either Roman or Arabic. Each of these identically hand-blued steel chapters is affixed to the dial by tiny feet, around 0.25mm in diameter. They sit eerily above the dial, which is neither enamel nor lacquer, but rather an incredibly hard form of zirconium ceramic.

This material is mesmerising: it has the perfect flatness of milled and polished stone, but with a depth that reminds me of the “snowflake” dials used by Seiko in their Grand Seiko models. Unlike anything I’ve seen before, it lacks the cold reflections of the Omega Dark Side of the Moon, and instead imbues the dial with a warm simplicity that it utterly entrancing. The zirconium ceramic is much harder than enamel, and the double layer dial is made up of two pieces, each less than 0.5mm thick. A circular aperture for the sub-seconds dial is cut into the upper piece. The inner minute track, along with the “Chas Frodsham, London” name, is deposited onto the dial in a permanent manner, allowing the dial to be handled, and even washed without damage. In fact, it should look just as good in a hundred years as it does today.

It’s clear that the firm has been very busy over the past decade. Alongside the carriage clock commission, they’ve also found time to complete Derek Pratt’s replica of Harrison’s H4, make a replica of H3 and assist in the manufacture of the world’s most accurate pendulum clock – Burgess-Clock B. On top of all that, they also found time to assist in the move of The Clockmaker’s Collection from Guildhall to a new location in the Science Museum. Throughout this period, work has continued on the wristwatch, but as a self-funded, truly independent endeavour, there’s been no reason to release a watch with which the entire team was not happy. This search for perfection has resulted in essential changes to the escapement, but has also allowed them to test these changes for extended periods of time. The result is an English-made Chronometer that quietly launched just after lunch on March 2nd, 2018.

The watch itself is 42.2mm across, and a shade over 10mm high. Lug-to-lug, the case is only 48mm, allowing it to sit on even the smallest of wrists in comfort. The large dial is surrounded by a relatively thin bezel and protected by a sapphire crystal. Whether in stainless steel, 18 karat white or rose gold, or even 22 karat hard-rolled yellow gold, the hand-made cases have an atemporal appeal, recalling 19th century pocket watches yet also looking entirely modern. The offset crown at 2.30 provides a jaunty angle to the watch, which is water resistant to 3ATM. But it’s when you turn the piece over, to see the movement under the sapphire display back, that the sculptural horology of the Double Impulse Chronometer is revealed.

George Daniels wrote about detached escapements in both The Practical Watch Escapement and Watchmaking, describing the independent double wheel escapement, founded on Breguet’s original échappement naturel. In the double wheel, each escape wheel is driven by its own mainspring, with a balance that takes impulses from both wheels. In the Double Impulse Chronometer Escapement, these mainsprings and the gear trains that follow the curve of the movement round to the two escape wheels, are entirely subservient to the large 14mm balance^ that takes centre stage. The two barrels are of similar size to the balance, and provide a reassuring 36-hour power reserve. Upon winding the watch, the theatre of the movement awakes, and the snail-shaped up/down indicator displays the power remaining within the mainsprings. This daily necessity will surely be one of the most pleasing aspects of owning a Double Impulse.

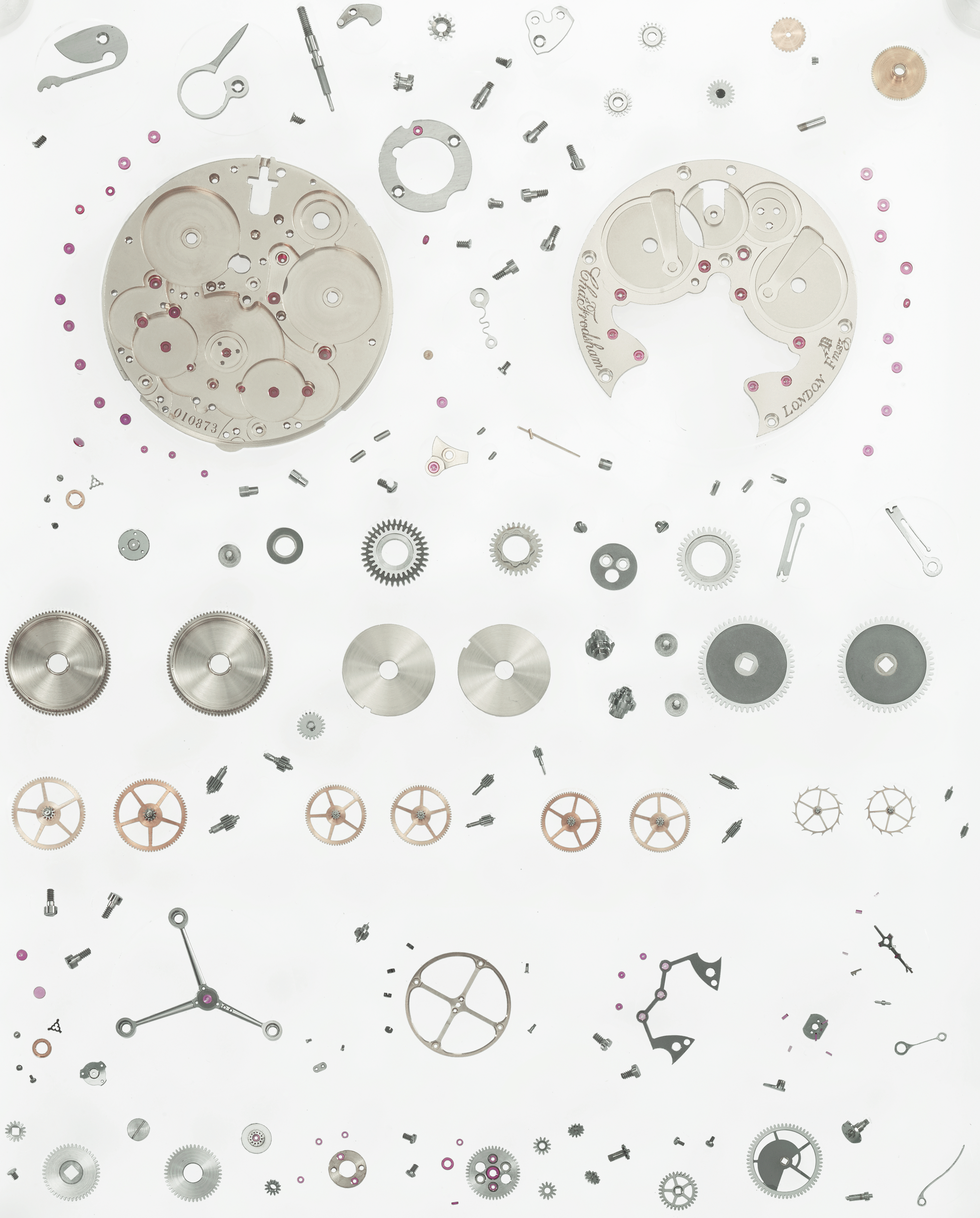

The components photo (above) illustrates how the plates have been cut to allow the gear train to better fit into the watch (and around the balance). As an aside, Daniels commented that the arrangement of the independent double escapement train that he used in his pocket watches “would be too complex for a wristwatch.” Flicking through Michael Clerizo’s wonderful George Daniels, A Master Watchmaker & A His Art, and the British Museum’s Collections online, one can see that the gear trains in (for example) the Clutton watch are probably placed more for aesthetic reasons than the need to save space. Like the Frodsham watch, Daniels also favoured lower-powered mainsprings; the Space Travellers both have a quoted power reserve of 32 hours. Daniels, famously, soon dropped the double wheel entirely, focusing on the co-axial escapement that first found its way into a Patek Philippe.

Of course, the central player in the 43 jewel Double Impulse is the oil-less escapement, which is utterly entrancing and completely bewitching. The balance has a frequency of 21,600 vibrations per hour, which is well beyond my visual acuity. The two counter-rotating escape wheels therefore appear almost to be unmoving below the balance, which pulses and breathes as the teeth release and impulse. In slow motion, it’s possible to follow the three locking stones on the detent, but for a better description, I’d suggest you read Justin Koullapis’ excellent article in the BHI’s Horological Journal – Charles Frodsham Wristwatch, Ten Years in the Making.

It goes without saying that each of the components within the movement is beautifully finished by the Frodsham team. Whether it’s the graining on the tiny titanium detent, or the black-polished arms of the balance bridge, each part looks superb under a Loupe System. Due to the amount of time that it takes to manufacture, hand finish and assemble these watches, production will be limited. The plates are frosted in the traditional English style and the train wheels are cut from hardened 18 karat rose gold. That huge balance is itself made from an unusual bronze with tungsten carbide timing weights. Speaking of timing, it should not be forgotten that Charles Frodsham & Co Ltd was (and continues to be) a maker of chronometers; the watch has therefore been developed as a consistent timekeeper, first and foremost.

Of the various dial and case options available to clients, it was the 22 karat yellow gold case that caught my eye; it’s an unusual colour that’s reminiscent of high-end pocket, rather than wristwatches. However, I also saw a rather special dial that was produced for one of the Frodsham directors. This differs from the production versions in that it displays two cyphers or medallions, recalling the Royal Warrants and timekeeping medals that have been awarded to Frodshams over the past two centuries (see below). Like the minute / hour track, these cyphers have been physically deposited on the dial in minute detail.

Although the watch was only officially launched at the beginning of March, a number have already been sold, and Frodshams expect to build between ten and twelve a year. A lifetime’s work has undoubtedly already been invested in this watch by the Frodsham staff over the past fifteen years, so I’m sure clients will be more than happy to wait a little bit longer. Prices will start at £60k plus VAT.

As a relative newcomer to this story, it feels as though I’ve largely missed out on the prolonged gestation and skipped straight to the birth. Charles Frodsham has delivered something rather special – an English-made production watch that is both a technical tour de force and a wonderfully bewitching piece of horological sculpture. To paraphrase the late Derek Pratt, ‘what will they do now?’

the #watchnerd

Disclosure: there is no financial relationship between the #watchnerd and Charles Frodsham & Co Ltd., and no remuneration or payment in kind was received (although Richard did make me a pretty decent espresso while we were chatting).

- The Solothurn, currently on display at the Clockmakers’ Museum, is a one-minute tourbillon, with constant force Daniels Double Wheel escapement, power reserve and thermometer.

** One of these prototype movements remains on display at The Clockmaker’s Museum, at the Science Museum in London.

*** The Frodsham wristwatch is not their first attempt to produce a serial design; a number of 12”’ lever movements cased in stainless steel by Dennison, and with silvered dials, were manufactured in 1947 (the majority as presentation pieces).

^ At the risk of getting overly prosaic, there’s a certain poetry in the watchmaking lexicon: words like balance, and poise spring immediately to mind when viewing the Double Impulse.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий